The Magic Bullet: City Pensions Back on Track

From the Royal Blue Columbia Police Department pullover and various police badges strewn across her desk, it’s easy to conclude that Shelly Jones works for the CPD. But she doesn’t drive a police car to work, chase criminals or carry a nightstick. She doesn’t even work in the department’s downtown red-brick fortress. Yet, she is a Columbia police officer — specifically, a lieutenant in the training and recruitment unit — and she loves her job. as one of a disproportionate number of officers hired in the early ’90s, Jones is up for retirement in July even though she isn’t sure of her plans yet. “If I do retire from here, I’ll probably get another job,” the 50-year-old says.

Jones joined the force well before the Columbia City Council unanimously approved a motion last July to make changes to city employees’ pension plans, a compromise between city officials and employee groups that was lauded as a magic bullet to solve the problem of significantly underfunded city pensions. Otherwise, she’d have five more years to go. In 2011, the Police and Fire pension fund and the fund for all other employees were 54 percent and 72 percent funded, respectively. according to Ken Shaw, an accountancy professor at the University of Missouri who has published numerous academic papers regarding private pensions, 80 or 90 percent is a healthy funding level. The changes, which went into effect oct. 1, 2012, are expected to save the city $50 million and increase funding levels to 80 percent within a 20-year period. “It doesn’t sound like much, but over 25 years it is,” Shaw says. “It’s a big, much-needed Band-aid that’s going to help,” says Patrick Madigan, a local investment representative. “But pensions are going to have the perpetual problem of needing money. They’re going to have to figure out a way to generate more money because people are living longer, and bond rates are so low.”

Funding the future

Public pensions have become a hotbed of contention as unfunded pension obligations nation-wide amounted to more than $2.8 trillion (and may be as high as $4.4 trillion) in 2012, according to the Congressional Joint Economic Committee. And, in the wake of dozens of municipality, city and county bankruptcies, local governments across the nation have had to pull out calculators and consider dramatic changes. According to an ABC story about Stockton, Calif., which declared bankruptcy on april 1, experts say pension funds have widely been managed “like the banking industry before the financial collapse by engaging in risky behavior and racking up unsustainable obligations.” “[The cities] are computing the funds as if the returns are going to be humongous in the future,” says Chester Spatt, professor of finance at Carnegie Mellon University and former chief economist of the Securities and Exchange Commission. “But these aren’t the returns society has. They’re nominal now, but pension liabilities aren’t being computed on that basis.” Madigan says historically, the majority of pensions have been invested in bonds, but with bond rates hovering at an all-time low, pensions have to reallocate portfolios and adjust their risk to get their expected returns. Spatt says one reason behind the nationwide issue is elected government officials’ hesitation to make significant changes “because it makes people angry” and “the problems will hit long after they leave office, and society will end up holding the bag.”

For example, Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker was recalled (and won again) shortly after he declared pension reform as a major issue. When Columbia Mayor Bob Mcdavid was first elected, he made pension reform a priority and appointed a task force to attempt to rein in the city’s liabilities.

Too old to work?

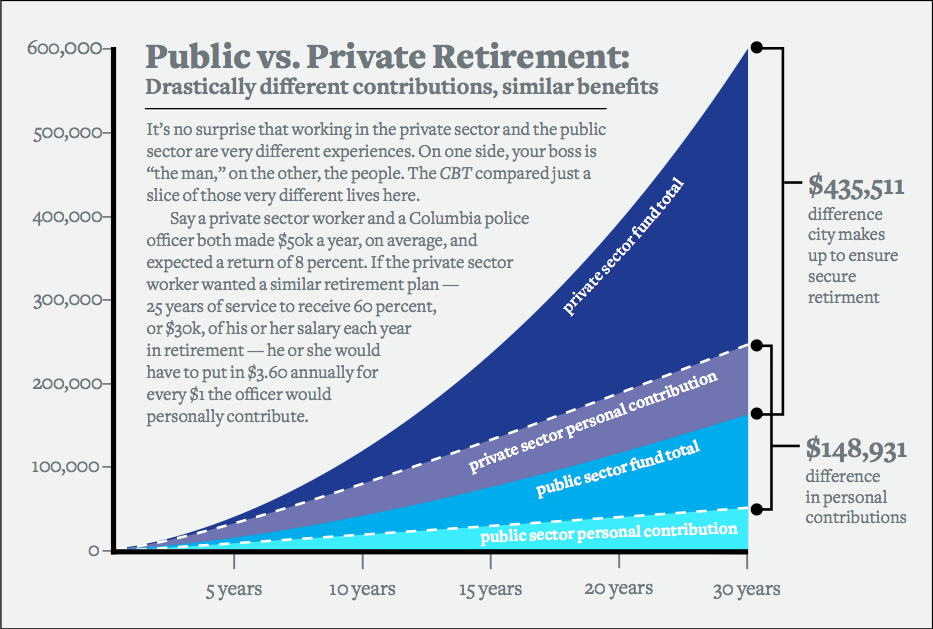

The changes still leave city employees with a defined benefit plan, which means the amount paid per month in retirement is a set number, regardless of actual investment returns; this is unlike the defined contribution plans such as 401(k)s and Roth IRAs that are popular in the private sector. Another major difference between public sector pensions and private retirement plans is the level of personal contribution, which among public pensions is relatively minimal or, in the case of all employees except those in the Fire and Police departments, non-contributory. Even Fire and Police employees, which under the new plan contribute between 4 and 4.5 percent of total compensation, previously earned back every penny of the money they put into their plans in 34 months and 9 months of retirement, respectively. According to Shaw, defined benefit plans have almost disappeared in the private sector due to their cost. “It’s a matter of survival in the private sector,” he says. “They have to find ways to cut costs to stay in business. There’s no backstop of, ‘We can raise taxes to fund this thing.’”

Madigan has a slightly different perspective on defined benefit plans. “Defined pension plans are defined as long as someone can keep paying it,” he says. “Historically, our society has seen them as something that will always be there, but they may not. there are so many moving parts that it can get very complicated.” For Madigan, fulfilling pension liabilities becomes increasingly difficult in the wake of higher-than-ever life expectancies, currently 78 years in the United States. “When our grandparents retired at 65, they died by 70,” Madigan says. “Life expectancies are longer, and people are now spending a third of their life in retirement.” A possible financial solution: Wait longer to retire. For example, in the case of a police officer with a typical salary of about $50,000 who con- tributes 4.5 percent for an additional 10 years, the total sum of his or her fund of personal contributions will more than double, decreasing the amount the city must contribute by around $223,000. Jones, of the Police department, says in their case, a 20 or 25-year career is optimal. “Police work isn’t an old man’s job; it’s a young man’s job. When you get to be 55 or 60, fighting bad guys on the street and jumping over fences takes its toll.”

Perk city

Despite obvious limitations, Shaw says it’s all about competition. “You need good salaries and benefits to hire good people, to the extent that the employees have options,” he says. For Jones, this was exactly what attracted her to mid-Missouri. “When I came to Columbia, one of the big draws was the retirement plan,” Jones says. “I really did my homework.” Madigan says that’s typically one of the biggest perks in public sector jobs. “If you ask anyone in the city what their best job perk is, it’s usually their pensions,” he says. “The problem is if Columbia tried to fix it, [other cities] will still be doing it the old way. If you know that a community will give you 20 years and done, you’ll make a nice life there, and when you’re 40, you’ll have the next 60 years to do what you want.” He says those firefighters, police officers and civil servants will simply find work somewhere else until there’s a “wholesale change across the country.” But at least in the case of the Police department, attracting new officers to its 12 currently vacant positions has already been difficult. In the past two years, it has lost 15 officers to retirement alone and 34 officers total. “That’s 34 brand new officers we’re hiring,” Jones says. the CPD’s turnover rate has been excessively high, Jones says, for the past few years. To combat this and a nationwide trend of decreased interest in law enforcement careers, the CPD has tried to expand its recruiting area from the Missouri-Kansas-Illinois tri-state area to nationwide. “We figured the bigger pool we have, the more applicants we might get,” Jones says. It’s become a cycle of trouble for the department, as those vacancies affect officers’ ability to take personal leave and increases overtime usage, which was more than $170,000 in 2012. According to John Blattel, the city finance director, that overtime increases eventual retirement benefits, though the only time it becomes truly problematic is in the case of “spiking” when “they work a lot of overtime during the three years their pension is calculated on.” But, ultimately, there will be some sort of effect, MU’s Shaw says. “More overtime means more pay, which means more problems down the line,” he says. “all these parts work together to change things, so it’s hard to pin down what will happen.”

Cleanup crew

According to Margrace Buckler, the city’s director of human resources, pensions and other benefits have generally been one draw to an otherwise unglamorous life of public service, but with dramatic changes to Columbia’s payroll to come, further questions arise. The city is currently working with a consultant, CBIZ Human Capital Service’s Compensation Consulting office of St. Louis, to revise and modernize its job classifications and pay data. Although Buckler says the new payment categorization will not decrease any salaries, it will likely increase payment for a number of positions. After research on average market salaries is complete, the city will have to determine how competitive its pay should be. “Making ourselves more competitive is the goal,” she says. “We want to make sure we’re positioned well to attract talent. [the city] is more interested now in competitive pay than in adding new benefits. We’re certainly more interested in operating more like a business.” However, she doesn’t see dramatic changes in the near future. “In 10 years, I don’t know what will happen to pensions,” she says. “But right now, we won’t go so far as to look just like the private sector.”

Although Madigan believes pensions are typically a better, safer bet than personal retirement portfolios, he questions their future. “The pensions are only going to get stricter, contributions are only going to continue to go up, and eventually pensions will be few and far between.” But the eventual effect the new plan will have on the city’s financial future remains a mystery. “it’s hard to speculate if it will solve the problem because things tend to unravel over many years,” Shaw says. “We just have to let time pass.”