Not Your Father’s Medical Practice

Once the norm, fewer doctors are going solo

As long as he can remember, Erin Meyer has wanted to be a doctor. “I explored other options but always went back to medicine,” he says. “My dad was kind of my inspiration.”

Now in his first year at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine, the 24-year-old Columbia native sees a landscape that’s changed dramatically since his father began practicing medicine. Among the changes is the end of what was once a cottage industry of independent physicians. During the past decade, an increasing number of doctors have left or bypassed small private practices for large groups and hospital-based practices.

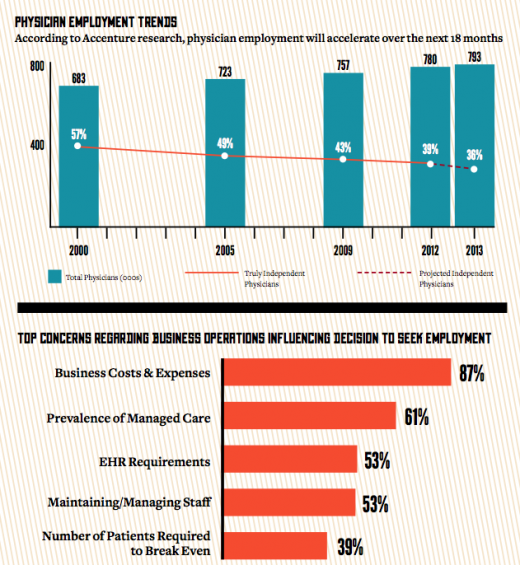

According to a report by Accenture, a management consulting technology services and outsourcing company, the number of independent physicians in the United States dropped from 57 percent in 2000 to 39 percent in 2012. The report predicts the percentage will drop to 36 in 2013. With the business of medicine becoming more complex — through the advent of cost-prohibitive Electronic Health Records and complicated insurance reimbursements, among other reasons — more doctors are sticking to what they went to school for: making people feel better.

For efficiency’s sake

For efficiency’s sake

“It’s a matter of efficiency,” says Priya Sadhu, a family physician working for a hospital-based group near St. Louis. Sadhu, whose father is a retired radiologist in Columbia, joined the group after completing her training in 2010. As the end of her residency neared, Sadhu found herself pulling back and forth between a large private practice and a hospital-based group. She didn’t even consider joining a smaller group.

Sadhu wanted the security of a two-year contract and guaranteed salary that a large group could offer. Her compensation package includes maternity leave, which she took advantage of when her son was born last year. Her call schedule, which for a primary-care physician can be arduous, is also quite manageable.

As for the day-to-day operations, she says she doesn’t have to worry about stocking inventory or how insurance companies will reimburse her. In addition, they have the budget to pay for Electronic Health Records (EHR), an expense that could be prohibitive for smaller practices.

“For me, I have the perfect setup currently,” she says. While interviewing for jobs, Sadhu says her focus was finding a balance between work and family rather than seeking financial success only. A generation ago, this was unheard of. But with women making up more than half of all physicians younger than 35, more young doctors (women and men) are giving serious consideration to their lifestyles.

“I wanted my priority to be with the patients rather than the administrative work,” she says. “Negotiating with insurance companies and filling out lots of paperwork takes away from patient care.”

Navigating the system

A downside for physicians in big groups is navigating the system. Administrators and physicians can sometimes approach issues from very different perspectives. As with any large company, working through the system and making changes takes time.

It’s one of the reasons that Tim McGarity, a local ophthalmologist, chose a solo practice. The American College of Physicians reports that solo practices attract fewer than 20 percent of new physicians. However, going solo still has strong advocates, among them physicians who value their independence.

“All along I wanted to be the captain of my own ship,” McGarity says. “I wanted to be directly involved in the business as well as patient care aspect of the practice. I knew I could take really good care of patients and didn’t necessarily need a larger facility to do it.”

When he completed his training in 2006, McGarity spent five years working in a hospital-based setting, which solidified his desire to be on his own. In 2010, when a local ophthalmologist approached him to buy his practice, he couldn’t resist.

“I noticed that Columbia was being served well by one specialist, and that was H. Kell Yang,” he says. The two of them transitioned for a year, and McGarity took over the practice in July 2011.

McGarity’s practice is a hybrid of sorts and offers a spectrum of services and sources of revenue. This approach lends itself to a solo practice more than some other specialties because it doesn’t rely solely on reimbursements from insurance or government programs such as Medicare.

Forty to 50 percent of his business is what he calls “free market.” Procedures such as laser corrective surgery, also known as LASIK, and advanced cataract surgery, an upgrade from the standard cataract procedure, can help offset the increasing costs that small private practices in particular are up against.

“Our insurance-based services are in many ways a community service,” McGarity says. One reason these services aren’t profitable for physicians in small practices is that they don’t have the lobbying or bargaining power of large groups and hospitals. As a result, small groups receive reimbursements that are significantly lower than what big practices receive for the same procedures.

EHR, which go into effect in February, are another area in which small practices can lose money. Because the costs outweigh the benefits at this time, McGarity has chosen to take a penalty rather than implement them.

“I’m a firm believer in EHR if you have a really good system,” he says. “Managing your data makes you a better physician. Within ophthalmology there’s not really a good system out there yet.”

McGarity says a couple of the companies are battling it out, and once they’re fine-tuned, they might work for him in the future.

“There are always going to be doctors who are business savvy, and specialties like ophthalmology and plastics lend themselves to small practices,” says Joe Meyer, Erin Meyer’s father and a local anesthesiologist specializing in pain management. “But put yourself in the shoes of an Erin. If you decide to go it on your own and hang a shingle, the startup can be slow, expensive and uncertain. Why do it when you can hit the ground running full speed by joining a big group?”

The business of medicine

Most doctors don’t love the business of medicine, Meyer says, and it’s becoming increasingly complex. In addition to negotiating with insurance companies, each of which has its own set of rules, physicians must submit their bills using a detailed coding system.

“The goal posts keep moving,” he says. “I’ve watched the medical community morph over the past 10 years. If you’re a surgeon, my advice is to join a surgery center group or start one of your own.”

Meyer worked for hospital-based groups early in his career and opened a solo pain management practice in 2002. In 2010, after adding partners and some nurse practitioners, he sold his practice to Surgery Center of Columbia. The decision offered him the best of both worlds: He and his staff still practice medicine as they had before, but his overhead has dropped dramatically.

“They’re not my employees or equipment any more,” he says. “My costs have been absorbed by an efficient, profitable business entity, and I’m able to focus on medicine.”

John Havey, a local orthopedic surgeon, shares these sentiments. In 2005, after more than 22 years in private practice, he and his partners merged with Columbia Orthopedic Group. COG, a private group of about 150 employees, acts as a medical service organization in which each physician develops his or her own practice.

“It’s the best thing I ever did,” Havey says. “All I have to do is be an orthopedic surgeon.”

When Havey completed his training in 1982, building a private practice was the norm for orthopedic surgeons. He recalls borrowing $100,000 right out of training, and with “no business training whatsoever” hiring staff, buying malpractice insurance and stocking the office. When computers became available in the 1980s, he had to act as his own IT guy and trouble-shoot his problems. He even had to wire the office himself.

“We all learned together and sometimes by just stepping in it,” he says. “We had to do it all, build a practice and start a business. In the beginning call was hard, every other night, every other weekend. Now I’m on call every three weeks. Honestly, I’m happier now than I’ve ever been.”

Havey says the greatest advantage to joining a group such as COG has been the ability to share costs. With changes such as the Affordable Care Act, also known as Obamacare, administrative costs are expected to increase while reimbursements for specialties decrease. Large groups can spread these costs and things such as Electronic Health Records and imaging over many doctors.

“This has been a really nice transition,” he says. “As a doctor you put so much into your career, but you get a lot out of it. Orthopedic surgeons don’t really save lives, but we improve the quality of our patients’ lives. It’s very rewarding.”