Risky businesses

When at first Dustin Vincke did not succeed at becoming a business owner, he kept trying. And then he tried some more.

When at first Dustin Vincke did not succeed at becoming a business owner, he kept trying. And then he tried some more.

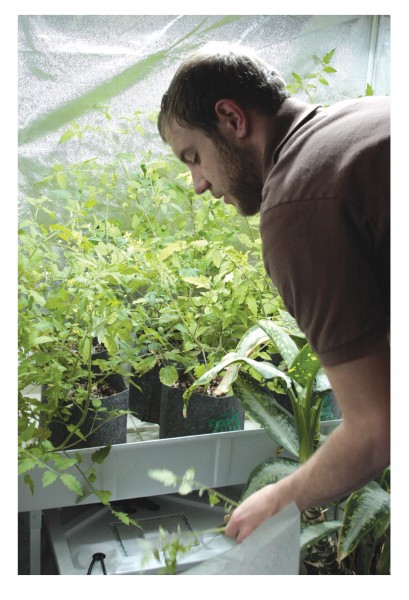

The old saying “try, try again” definitely holds true, says 24-year-old Vincke, who took over as sole owner of Heartland Hydrogardens, a retail supply shop for garden enthusiasts. “I have always known that I would own my own business someday,” he says. “I just didn’t realize all the work it would take to get here.”

For Vincke it took three trips over a span of almost two years to the Bank of Missouri before lendors would approve the loan he needed. But with detours that included professional business counseling, a year of apprenticeship with no pay, and several months as a part-owner, money lenders finally began to see him as “bankable.”

For now, he’s a one-man show, working all day, every day. He is the store clerk, the bookkeeper, the janitor, the marketing strategist and all jobs that lie between. Even when he’s not officially on the job, it’s always on his mind.

Although Vincke took a big financial risk, he says he knows that if he continues to focus on the business, it will survive. And while he earns slightly more than he did working an hourly wage, there is another payoff: “It is great to not be dependent on somebody as your employer,” he says. “Any mistakes I make are mine; any success is mine.”

Starting from scratch

Starting from scratch

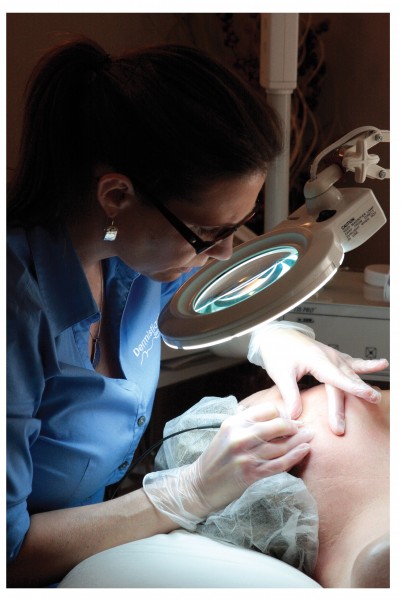

Susan Lueders, owner of Dermistique Face & Body, ventured out on her own back in 2008, just as the economic recession was beginning to wreak havoc on small businesses across the nation. With more than 10 years of experience in the field, she had built a loyal client base, although many advised against creating a startup at that time.

But with a business degree from Columbia College, she understood the basics. And for years, she put her dreams on hold. She evaluated her financial situation on a regular basis, not always pleased with the results.

Today, she attributes her success to that patience. By not jumping in with haste, she was able to put money into savings and piece together a solid business plan. In that, she was able to get started without a bank loan, using the small savings she had accrued and financing the rest on a zero-percent-interest credit card that was paid off within its first year. To keep costs down, she and her husband Aaron have handled much of the construction, design and marketing on their own.

Now more than four years into the business, she works harder than ever, and still doesn’t pay herself what she earned while working for others. For now, the profits go back into the business. For her too, the sense of autonomy is the payoff for the risk and long hours.

“It hasn’t been easy, but I am amazed when I take a moment and look at this business,” she says. “We have planted this seed, tended to it and are watching it grow.”

To build or buy

When asked if it’s riskier to start a business from scratch or buy an existing business, Chris Rosskopf doesn’t have to think long. Without a doubt, he says, providing lending for business acquisitions is much safer than banking on a start-up.

“When a person makes a business acquisition, as compared to building a startup, that business has already proven itself,” says Rosskopf, assistant vice president of commercial lending with Boone County National Bank. “There is an established value. We already know whether it can generate cash flow. And because of that lower risk, it’s easier, in general, to get a loan.”

Rosskopf’s best advice for clients interested in buying a business: Retain the previous owner’s expertise for as long as possible. They have already learned from trial and error — and that knowledge can save new owners a lot of grief. Also, he adds, keep the former owner’s employees on staff. They know the business routine, which can be a tremendous benefit to new owners.

Keith McLaughlin, senior vice president of small business lending for The Bank of Missouri, seconds Rosskopf’s advice. Established businesses come with name recognition, an established cash flow, and trained employees; and with all that comes a better chance of success.

What’s it worth?

One difficulty in buying an existing business, McLaughlin says, is in determining its actual value. Owners of startups put countless hours of “sweat equity” into a business and often believe it to be worth more than its actual value. While that labor does have value, putting a price tag on those efforts can become tricky. And when a buyer pays too much for a business, it becomes that much more difficult to pay off.

But the truth is, says McLaughlin, all kinds of business ownership are risky in today’s market, including franchises. While most people tend to think of franchise ownership as a “sure bet,” it’s been his experience that with modern-day chains the financial risk is similar to that of a start-up. What he refers to as “average” franchises (those not part of global entities such as McDonalds, for example) offer some advantage through name recognition, which helps attract business. But other than that, there are often hefty fees involved and almost no structural or financial support.

McLaughlin gives the example of a father who purchased a historically successful franchise for one of his children, but paid too much. As a result, they soon found themselves unable to afford the employee payroll or monthly expenses. In an effort to revive the business, they decided to relocate, which created more debt. Shortly thereafter, the once-thriving business was out of operation.

“It is almost impossible to do too much research before buying a business,” McLaughlin says. “The decisions a person makes up front greatly determine whether the business succeeds. Pay too much, and there is trouble from the beginning.”

Building a start-up has its own set of risks. The most obvious, McLaughlin says, is that there is no income stream. To go into business, a person should have enough money saved to cover operating costs for at least a year or more. Buying the business is only the beginning; and it’s crucial to factor in the other expenditures. “Cash is king,” he says. “It’s the lifeblood of any business. Without it, you’re gone.”

The most common mistake, McLaughlin says, happens with clients who decide they want to go into a particular area, but have never worked in that field. In his experience, those decisions are almost guaranteed to fail. When a person doesn’t enjoy his or her work, it’s highly unlikely the business will do well.

“When people want to go into business for themselves, the risk is always high, but it’s possible with the right mindset and action. People who are serious about their efforts, who tap into their available resources, who put in the extra hours—they can succeed,” McLaughlin says. “People need to know that when you own your own business, you’re the president of the company as well as the chief janitor.”

Good business lenders are serious about insisting that clients meet the bank’s expectations, he says, and there is good reason for that. Banks want to be a party to success—not failure. “The worst thing a lender can do is provide loans for clients who aren’t ready. We all saw what happened with the housing market, with people who were unable to make their payments. That same thing could very easily happen with small business.”

Research pays off

Whether a person decides to build from the ground up or take over from a previous owner, gathering the right information is critical to success. When they aren’t 100 percent confident about a client’s proposal business plan, both Rosskopf and McLaughlin direct their customers to The Missouri Small Business & Technology Development Centers (SBTDC), an agency that provides one-on-one counseling at no charge.

“One of our main functions is to help people examine the feasibility of their business idea,” says SBTDC Director Virginia Wilson. The office guides them through the process of writing a business plan and asks the tough questions that they often don’t ask themselves:

• Is there a market for my product?

• Will it be profitable?

• What are my monthly revenue projections?

• What are the operating costs?

• How much competition is there, and who are my competitors?

• Who are my customers?

The centers also offer a program for financial analysis and trending. Using three years of past financial records, the office is able to create a picture of where a business is headed if it continues with no changes, or if there is some redirection. Some clients take advantage of the program yearly to help ensure the business is making healthy decisions.

Most small business owners look at the bottom line, says Wilson; and if there is some small profit, they are satisfied. But those are known as “lagging indicators,” and can be misleading regarding the overall business analysis. “What is more important is finding what is driving those figures. If a business is in good financial shape, it’s important to know why they’re good. And if they’re not good, it’s crucial to find out what needs changed. There could be issues with pricing or inefficiencies in operations. There are any number of factors that can influence your business.”

Regional Economic Development Incorporated (REDI) is another free resource available to business owners. Serving Columbia and Boone County, REDI’s main objectives are to attract new businesses to the area, retain key employers and assist companies in creating new jobs.

In its new downtown facility, the REDI office will offer a 30-person meeting room to provide training workshops for current business owners and those considering ownership. But perhaps its greatest resource for new business owners is a database of property information used to pinpoint demographic and marketing information based on a specific location. The system can create analysis reports based on radius or drive time, offering information about the average disposable income of a certain area, populations and other specific factors.

“It’s all part of what’s necessary in deciding which path to take,” says REDI President Mike Brooks. “Whatever direction a person chooses, owning a business is a big investment—and this information is crucial in deciding whether an idea is bankable or not.”

The ‘you’ factor

McLaughlin says that, even with his 25 years of banking experience, there is no fool-proof way to predict if a business will succeed. He gives an example of a working couple who came to him several years ago, wanting to take out a loan. The two had steady, middle-class incomes and could comfortably afford children, a house, cars, vacations and other costs of living. They had decided it was time for both to quit their jobs and focus on starting their own business.

Skeptical about both people quitting work, McLaughlin offered them a compromise: One person would continue working, the other would begin working on the new business, and he would grant them the loan. They declined his offer.

“I ran into them years later and am glad to report they are now running one of Columbia’s most successful catering businesses,” McLaughlin says. “They were set on both people quitting, and they made it work. So there you have it. Nobody knows and success or failure depends very heavily on the individuals themselves.”

Most business and lending experts agree: In deciding whether to create a startup or purchase an existing business, there is no sure bet. There is only right or wrong for the individual.

“One size doesn’t fit all,” Brooks says. “We can’t know which path is best without analyzing the individual’s skills, interests, needs, etcetera. It depends on the situation. It depends on that person’s appetite for risk.”

If you’re a tradesman, he explains, you probably don’t have to buy a lot of inventory. Your business is based largely on your labor. In that case, a startup might make the most sense. If you’re a retailer, then there is a lot of inventory involved, as well as marketing and publicity costs. In that case, it might be more advantageous to take over where another owner left off.

Why risk it?

McLaughlin says it happens all too often: Clients have the misconception that when a person owns his or her own business they are wealthier. But the truth is, most new businesses don’t begin to turn a profit until at least the second year. In the meantime, owners tend to work all day, every day, and earn less than their employees, if they’re fortunate enough to have hired help.

Owning and operating a business isn’t for everyone,” McLaughlin says. “Working for others is good too. If you can get in the right environment, find a supportive boss who gives their employees room to grow, who encourages them to use their talents and ideas, then it can be very rewarding. It’s very possible to make a good living working for someone else. And if you have that, why risk it?”