Solar film brightens 3M’s future locally: Plant expansion to create 120 jobs, revitalize factory

by Jacob Barker

October 29, 2010

Inside, the production space is more than half empty. On both sides of one hallway, rooms the size of basketball courts were left vacant as the company scaled down US production of goods made cheaper overseas.

With the expansion of renewable energy technology at 3M and the proven adaptability of the local workforce, the once bustling factory is showing signs of renewal.

Last week, workers began preparing the spacious production rooms to accommodate equipment for new products and employees that will give the city’s wilted manufacturing base a much-needed jolt.

“All these spaces are going to be filled with people and equipment over the next 18 months,” plant manager Bill Moore said.

3M is reinvesting in its Columbia factory and planning to add about 120 jobs by 2012. The Minnesota-based company is pumping more than $20 million into the facility to add new products and relocate existing ones here. The only product the company has announced so far is one that industry analysts see as having a long, successful lifespan: protective film for solar panels that can be used instead of traditional glass casings.

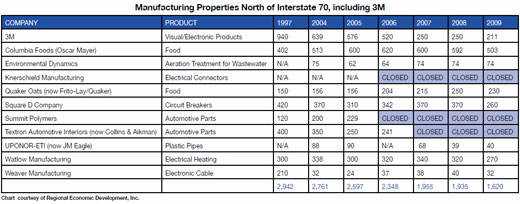

That’s good news for a plant that has had little of it during the past 15 years. Once one of the largest manufacturing operations in the region, the plant’s workforce plummeted from 940 in 1997 to 210 today as its electronic products became cheaper to make in Asia.

The past decade has been rough on 3M’s neighbors as well. Layoffs became a regular occurrence in the city’s northern industrial corridor; the number of workers in the factories on Route B and nearby fell by more than 1,300 since 1997, to 1,620.

Unlike some of its former neighbors, the 3M plant managed to stay open. But it is a shadow of its former self, and as electronics manufacturing continued to move offshore, it seemed only a matter of time before the Columbia factory closed.

“Products all have a life cycle,” said Bernie Andrews, vice president of Regional Economic Development Inc. “3M rode out those previous products as long as they could.”

REDI President Mike Brooks said, “I’ve been extremely impressed with (the management team’s) desire to rebuild this facility as a strong manufacturing facility in the Columbia area.”

The engineers and skilled technicians and the longevity of the workforce make the company team extremely adept at ramping up pilot projects to commercial-scale production, Moore said. That, plus the availability of open space within the facility, made Columbia the best fit for a number of products, he said. In addition, the state is offering more than $4 million in tax credits and assistance.

“I think we had a lot of things going in the right direction,” Moore said. “It’s a really good manufacturing site.”

Solar panel innovations

For the solar project alone, Moore said 3M is investing about $24 million in new equipment, building retrofits and workers. Called Ultra Barrier Solar Film, the new product is designed as a protective coating for thin-film solar panels. Thin-film solar panels are lighter and easier to make than the traditional silicon-based panels.

But most thin-film producers struggle to compete because the material used in the panels is less efficient in converting sunlight into energy, which ultimately raises costs. To get the same amount of energy, more panels, and thus more labor, are needed. The attraction of various thin-film technologies, though, is their potential to be more efficient at energy conversion and cheaper to manufacture.

Almost every company that makes either type uses glass to protect the photovoltaic panel. 3M is betting that companies will begin replacing glass with its protective film. For one, it’s lighter than glass, so more panels could be installed on a roof, for example. And second, it’s flexible, so solar panels could be used on surfaces that rigid glass couldn’t. Moore said he thinks the product could be a big win, and the pilot project has shown it works.

“There are end-users, and there’s demand for the product,” Moore said. “Certainly, solar film is a product the market has decided is a very necessary enabler for solar energy to go to the next level and really expand significantly.”

The investment in the product and the publicity the company has given it are good indications that demand for the product exists, according to Adam Fleck, a Morningstar analyst who follows 3M.

“This has been a company that’s been very conservative over the past several years, really since (Chief Executive Officer) George Buckley came in in 2005,” Fleck said. “They haven’t gone out and tried to chase end markets.”

The solar project is part of the company’s push to gain a bigger foothold in the renewable energy market.

At the beginning of 2009, 3M created a renewable energy division within its corporate structure. Although the division is small for the company (likely less than $1 billion, Fleck said), it has grown rapidly. The division led the company’s industrial and transportation segment in 2009 sales growth, and last quarter it grew by 71 percent.

During the last conference call, management talked about how the renewable energy division was “butting up against capacity constraints because of the demand in this industry,” Fleck said.

“It’s an area management has highlighted several times, and it’s definitely an area of excitement,” Fleck said.

Solar energy is usually the most expensive type of energy to produce. Thin film, in particular, struggles against silicon panels, especially now with the low price of the mineral, said Stephen Simko, a Morningstar analyst who follows the renewable energy markets. Because more thin-film panels are needed to produce the same energy as silicon, the rooftop market has been dominated by silicon, he said. A lighter material than glass could help open up that market and reduce installation costs.

“What thin film is really struggling with is getting their costs low enough where that installation penalty is overcome,” Simko said.

Fleck thinks 3M could contribute to the solar market by helping push down costs. The company is known for its highly efficient manufacturing processes and its expertise in producing industrial products similar to Ultra Barrier, he said.

“It’s really in the wheelhouse of the company as far as producing film,” Fleck said. “They do it for LCDs; they do it for computer screens; they do it for a number of other applications all the way up to 3-D and touch-screen. This just falls into that bread and butter of producing film cheaply.”

Experience pays off

The Columbia plant’s history underscores that argument. When it first opened, the 160,000-square-foot facility made film for its Visual Systems Division. Years later, it began producing the Fresnel lenses for use in overhead projectors, a manufacturing technology that is involved in the production of the solar film, Moore said.

“All the overhead projectors in the world used to be made right here,” Moore said. “And what we learned from that has really helped us be a part of this opportunity here with solar film.”

Although glass accounts for only 5 to 10 percent of the cost of producing a solar panel, Simko said, 3M could drive that down even further if its film can achieve economies of scale glass couldn’t. And the investment capital flowing into thin film right now could make that possible.

During the past several quarters, Simko estimates more than $1 billion has been invested in equipment for the production of thin-film panels. There’s a huge investment cycle ramping up for the industry, he said, and many solar startups are expected to begin production in 2011. In Silicon Valley, for instance, clean energy companies took about 45 percent of the Bay Area’s venture capital in 2009, the Wall Street Journal reported.

“There is a huge amount of production capacity coming online globally of just different thin-film solar modules,” Simko said.

Thus 3M will have the opportunity to supply plenty of new customers, at least during 2011, Simko said.

Almost every producer of thin film uses glass panels. But the biggest prize of all for 3M would be First Solar, the only thin-film company that has posted big profits, Simko said. If 3M’s film is cheaper than the glass First Solar uses, that would be a huge supplier contract for the company and a potential game changer for the industry. But Fleck and Moore both noted that it will be a tough market to compete in.

“If they’re able to get costs down in this business, it could be a tremendous breakthrough for the industry, but it is competitive,” Fleck said.

Moore said that will be the Columbia team’s challenge — making sure they develop the most cost-efficient production model for the film so it can compete globally.

But can the city count on the production staying here rather than moving to a cheaper labor market once the process is developed and time-tested? Moore says yes.

“The level of investment that 3M is making in commitment to Columbia is quite significant, so we don’t have a desire or a plan to move this out of Columbia in the future,” he said. “The desire and intent is to keep it here.”

And there are other products coming. The plant is expanding so it can build several other products for the health care industry, Moore said, though he could not yet disclose more details.

“They come from a variety of different sources,” he said. “Some of them have mature markets already, with customers already buying that product. Some are brand-new, out-of-the-box.”

Construction should begin by the first quarter of next year, he said. In the meantime, he and the plant’s team are still fine-tuning the production process for Ultra Barrier. He and others in the plant know the process has to be flawless if it is to stay globally competitive, both within 3M and with other companies.

“I want the next generation of solar film to be here — and the next and the next and the next,” Moore said. “But the competition will be out there.”