The drawn-out demise of Columbia’s passenger train service

by Al Germond

July 23, 2010

I was one of the last incoming passengers on Norfolk and Western Train No. 37, due to arrive at Wabash Station from Centralia at 5.20 p.m. The only other people inside the old day coach were a conductor and one other passenger who was gingerly holding what looked like a cello.

We rocked and rolled for nearly an hour over that last 21.7 miles of prairie down the Columbia Branch on a gloomy Monday afternoon. What followed for me was grabbing a Twin Chopped Cow at Ernie’s Steak House before heading to my 6 to 10 p.m. shift at KFRU Radio.

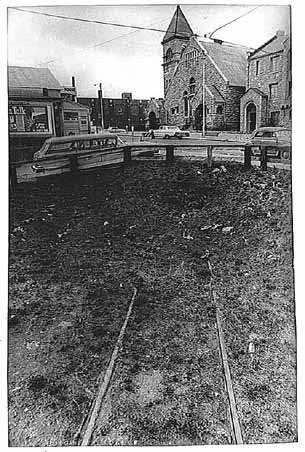

Columbia’s Wabash Station opened in 1910, the year Mark Twain died and Halley’s Comet reappeared after an absence of 86 years. Columbia has the somewhat dubious distinction of being one of the nation’s largest metropolitan areas without any main line rail service, but the city had the good sense to preserve the old downtown depot and turn it into a bus station. The Wabash Station celebrated its 100th anniversary on June 16.

Now there’s excitement about plans for a dinner train to run on weekends to Centralia and back. The Columbia Star, with two locomotives and four Southern Pacific dining cars, is expected to start taking passengers on round trips in August. But they’ll be loading and unloading at the COLT Transload facility on Brown Station Road in north Columbia rather than at Wabash Station, where railroad tracks were torn away long ago.

My final trip to Wabash began at 4:20 p.m. the previous day. I boarded a Penn-Central train in Newark, N.J., that was hauled by my favorite article of railroad motive power, the classic Raymond Lowey-designed GG-1 electric engine. No. 4938 still bore traces of PRR Tuscan red varnish. Memories ring out of the stationmaster calling out his gazetteer of destinations: “TrenTON, Naaahth PhilaDELphia, Haaarisburg, AlTOOnah, PITTSburgh, CohLUMbus, IndiaNAPolis, Terre HUT and Saint Loooisss.”

After ditching the electric GG-1 engine at Enola outside of Harrisburg, the train continued on to St. Louis and arrived at about 1 o’clock at Union Station, which was already somewhat down at the heels. Reviewing snapshots of that once grand train station contrasts with images of capacity crowds on its platforms only a few years before.

After a short wait, it was on to Centralia. Train No. 209 left at 2 p.m. on Track Four, with stops at the old Delmar Station (now part of the St. Louis Metrolink system), St. Charles, Montgomery City, Wellsville and Mexico.

Centralia — the final stop for me on the main line — was once this area’s big deal in railroading. A station as magnificent as Columbia’s own used to grace the north side of the tracks, and there was an impressive amount of activity there as main line passengers transitioned to the Columbia Branch and vice versa. Alas, the old station is gone, as are many others across the land, and there is little left to remind us of the once great times for the choo-choo in America.

The decline had been going on for years. In 1969, the Penn-Central was stumbling because of the previous year’s long planned but ill-fated consolidation of the New York Central System and the Pennsylvania Road. The enterprise tottered into bankruptcy in June 1970. The following year, the National Railroad Passenger Corp., or AMTRAK, rescued what was left of the remaining railroads’ dwindling passenger service.

Taxed to their virtual operating limit during World War II, the railroads gamely tried to compete during peacetime with airlines and government-financed highways, including the web of new interstates, but they moved increasingly into the red. Railroading had its own specific Chapter 77 within the federal bankruptcy statutes, and one prominent area operation, the Missouri Pacific, operated under receivership for decades beginning in the Great Depression.

Postal subsidies began disappearing in the 1950s. Operating burdens included property taxes and featherbedding, a practice in which unions proved intractable on a variety of make-work issues. Railroads had been paring passenger service for decades, and the exasperation continued after Norfolk and Western bought the Wabash in 1964. Various public service commissions regulating the railroads ignored requests to help end these deficit operations, and ultimately they had to stop hauling people around.

There’s a side note of family history in laying out the North Missouri Railroad during the 1850s. My great-grandfather Henry S. Germond of Brooklyn, N.Y., was part of the engineering survey party that was working east of Centralia when Mr. Wentz of the railroad company — after whom Wentzville was named — advised him of a relative’s death and he hurriedly left the area.

A clutch of my grandfather’s letters and a surviving survey drawing underscores why railroads seek out the most level terrain possible and a possible reason why the line avoided Columbia.

From a surveyor’s perspective, a plausible obstacle would have been the expense of building a trestle across the Loutre River valley near Mineola, 40 miles east of Columbia. Centralia got the line, which satisfied a need that the route serve Boone County, because construction was frankly simpler and less expensive.

Other accounts detail various political and funding considerations as to why Columbia never got main line rail service. They included fear that the line would become an escape route for area slaves.

Denied the main line, Columbia ended up with a rather busy and profitable branch line just the same. The November 1939 issue of “The Official Guide of the Railroads” — 1,588 pages in all — shows a total of five outbound Wabash trains and four inbound to Columbia each day that connected with the main line in Centralia. From there, the Wabash ran trains to St. Louis, Kansas City, Omaha and Des Moines. Not so ironically, the Wabash was already bankrupt and operating under the protection of two receivers.

The service arrangement from Columbia’s other branch line railroad — the Missouri-Kansas-Texas Lines, which was not bankrupt at the time — was considerably more modest. A quartet of trains traveled 8.8 miles down to the main line at McBaine, all of them arriving and departing at rather inhospitable times in the middle of the night.

Undeniable is Missouri’s nationally significant trans-state freight lines largely under the Burlington Northern-Santa Fe flag.

One possible light at the end of railroading’s tunnel is a system of high-speed passenger trains, but the staggering cost renders them out of consideration for a long time to come.

History records a trans-state railroad line that never came to fruition because it was poorly timed with respect to various economic cycles. As more is uncovered, it will be detailed in this space. Regardless, it is important that Columbia sit at the table to discuss future high-speed rail prospects. There might be significant precedents that help ensure its participation in this important function.