From the Roundtable: MU lab explosion a reminder of experimental dangers

The recent explosion and fire in Schweitzer Hall on the University of Missouri’s white campus reminds us that the practice of scientific research is fraught with risk.

The explosion on June 28 was caused by the ignition of hydrogen gas in a chamber used for working with bacteria, a Columbia Fire Department captain said. Three students and a lab technician were burned and hit by shrapnel, and one suffered a serious impact injury.

Looking forward, we want to be assured that all is well on the university campus.

However, the incident triggered memories of how MU had to close and decontaminate Schweitzer decades ago and, during this decade, another campus building dedicated to the study of chemistry, neighboring Schlundt Hall.

During a segment of the Columbia Business Times Sunday Morning Roundtable on KFRU after the latest accident, a caller to the radio station also recollected that both buildings were contaminated at different times. In the 1970s, Schweitzer Hall was taken apart to the bare walls and probed minutely with a Geiger counter until all traces of radioactivity had been found and disposed of. Schlundt Hall was decontaminated after radiation was discovered five or six years ago.

Wow! Think about it: radioactive substances contained in two university buildings where during the years tens of thousands of people — professors, instructors, students, staffers and maintenance workers — had circulated in surroundings that just about everyone assumed were perfectly safe.

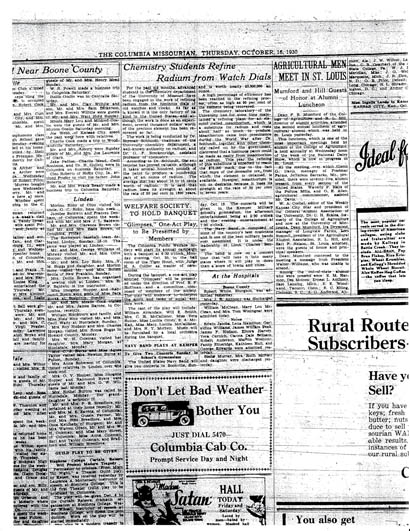

Months ago, I came across a brief item in the New York Times, Oct. 19, 1930, with a headline that said, “Chemistry Students Refine Radium From Watch Dials.” The article was picked up from a Columbia Missourian article from three days before, which said students in MU’s chemistry department “have been engaged in the work of refining radium from the luminous dials of old watches and clocks.” The Times described it as “the only factory of its kind in the United States” and said that several thousand dollars worth of the element had been recovered in the six months since the work had started. The radium was the basis for the luminosity of the paint used on the dials.

Placed in the context of the gathering economic Depression, any supplemental income to the university in 1930 would have been welcome. This was a time of managerial turmoil at MU. President Stratton D. Brooks had been fired rather unceremoniously, a scapegoat after publicity about an instructor’s sex survey that was innocuous by today’s standards. During the ruckus the state Legislature forced Brooks out, and the presidency went to School of Journalism founder Walter Williams.

The history of radioactivity at MU probably began in 1903 when Dr. Herman Schlundt (1869-1937) arrived in Columbia with a freshly minted Ph.D. from the University of Wisconsin. Elevated to full professor in 1907, Schlundt authored popular experiments in chemistry textbooks and in 1909 wrote a paper about radioactivity in mineral waters in Yellowstone National Park.

Schweitzer Hall was built in 1912, and a decade later the chemistry department was expanding beyond its capacity to handle the increased number of students and amount of research work.

On Feb. 4, 1922, the Columbia Missourian printed a story with the headline, “Plans Ready for New Hall of Chemistry.” The building was to cost $125,000 and include “a specially equipped room for research work in radium [that] will be in the basement.” A few years later, the MU catalog shows a three-hour course, “Radioactivity and Structure of Matter,” taught by Dr. Schlundt. One assumes the radium laboratory was in full operation in the basement of the building eventually named after him.

In 1924, William McGavock of Springfield, Ill., (1906-1985) moved to Columbia and entered the university where he received B.A. and M.A. degrees in chemistry. McGavock worked with Schlundt to develop a laboratory “for refining Radium and Mesothorium,” which, according to one Internet source, “at the time was the only lab refining the Thorium series, and notable scientists such as Mme. Curie obtained Thorium from that lab.”

The article from the Oct. 16, 1930, Missourian noted that the university was refining a substance called mesothorium derived from the radium scrapings of discarded watch dials and was expected to earn $75,000 from this endeavor in 1930.

Then something happened, and here is where the mystery deepens.

Shortly after MU’s operation was spotlighted in the national press, the lab was shut down.

Perhaps knowledge of the so-called “radium girls” case in 1928 at the US radium plant in Orange, N.J., had an impact. Pending further investigation, it’s pure conjecture at this point.

In the radium girls case, female workers were fatally poisoned in the factory, where they had been painting radium on watch and instrument dials since 1917. The case, according to Wikipedia, “established the right of individual workers who contacted occupational diseases to sue their employer.”

One wonders about the immediate aftermath of whatever was going on within the confines of Schweitzer and Schlundt halls. Something stopped this work perhaps rather quietly and with little, if any, press attention at the time, but it definitely ended leaving contaminated buildings for future generations to deal with.

One wonders about the health and eventual outcome of anyone who worked in the radium lab. What about Schlundt’s residence on Westmount Avenue? Were any radioactive contaminants found there? Was Schlundt’s death in 1937 related to working with radium and its derivatives? These are valid questions for further research.

As for the present, we can only go by what we are told by university authorities and assume the complete safety of the campus and, as mandated by law, full disclosure of all research activities and cooperation with the Columbia Fire Department and other public safety agencies.

As the fundamental underpinning of any research institution, scientific study at the University of Missouri continues to yield a great number of exciting projects to talk about. There are increases with patenting and licensing activities and serious income implications. Stories from the past should not unduly alarm us, but we all share the responsibility that the university’s research activities be conduced with complete safety and the assurance of well-being to the public.