Vertical Group scam destroys friendships

It has been about a year since Columbia resident Mike Trom spoke with his former friend and neighbor Nathan Reuter, founder of Vertical Group LLC, formerly located at 3210 Bluff Creek Drive.

The encounter between the two men at a hearing at the federal bankruptcy court in Kansas City was brief; it wasn’t much of a conversation really. It was more of an exchange of pleasantries, Trom said, “and that’s about it.”

Trom said he and Reuter were friends for seven years before Reuter approached him in 2004 about investing through Vertical Group. They hunted together, attended neighborhood dinner clubs together, their children played together. Trom said he once helped Reuter build his garage.

When they were still neighbors, Reuter’s son was returning to Woodbury Court in southwest Columbia from the Mayo Clinic after a heart operation, and the Troms decorated the neighborhood to welcome him home.

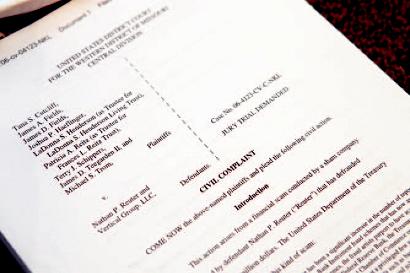

In the years since, Trom and Reuter have been on opposite sides of a long court battle that involved several of Vertical Group’s officers who have been sentenced to probation or prison for their roles in an investment scam that brought down the company.

Dow decided that Reuter should pay up for his role in the elaborate investment scheme that took millions from investors — and friends — who trusted him. And on May 19, the judge converted Reuter’s Chapter 11 bankruptcy filing to a Chapter 7, which means his assets could be liquidated to pay back Trom and eight other investors who claim that Reuter scammed them.

The investors involved in the bankruptcy case lost a total of about $917,000. Dow said they are entitled to get that money back, plus $2.7 million in damages and attorneys’ fees.

In all, Vertical Group was able to pull in more than $2 million from about 40 investors from across the country. According to court documents, Trom was the first of the nine investors involved with the lawsuit to give money to the company.

The former location of Vertical Group is now home to a law firm, and Reuter is working as a carpenter in Columbia.

But in late 2004 and early 2005, these offices were a place of big talk and big promises — a place where investors from all over the state and the country were told their five- or six-figure investments could be used to acquire standby letters of credit, and they could become millionaires overnight.

Because he claims to have lost money in the deal with Trom and that Vertical officers had misinformed him, Reuter has maintained that he, too, was the victim of a scam.

Before the bankruptcy judge ordered him to pay the investors, Reuter was unable to defend himself from accusations made against him in a lawsuit by the investors and then sought bankruptcy protection.

He has never been found guilty of any criminal charges.

“If he were guilty, he would have been prosecuted,” said his lawyer in the bankruptcy case, James Daniels of Kansas City.

“…a sharp business acumen”

Reuter, 51, is originally from California, Mo., a town of about 4,000, located 60 miles southwest of Columbia. He graduated in 1980 from the University of Missouri, where he had been a member of the Delta Upsilon fraternity, with a degree in agricultural economics.

From there, he went to work for AmerenUE for 13 years. He managed inventory control for the company’s nuclear power plant in Callaway County. But Reuter had bigger aspirations.

After he left Ameren, Reuter began working in real estate and started up a few businesses in Columbia, according to court documents. He filed with the Missouri Secretary of State to start The Tiger Club LLC, located at 1116 Business Loop 70 E., in 1992. He then started up Mr. Tidy Car Wash, formerly located in southwest Columbia at 3715 Sandman Lane.

Reuter formed Liberty Financial Corporation in 1999 in Springfield, according to court documents and documents filed with the Missouri Secretary of State. It was around this time that Monte Chilters of Springfield came to work for Reuter.

Chilters, who handled residential real estate loans for Reuter’s company, said he was interviewed by Reuter to work for the company. He described Reuter as a “sharp guy” and “easygoing.”

More importantly, Chilters said, he had heard good things about Reuter’s reputation in the local business community, namely that Reuter had “the Midas touch.”

“Everything he touched turned to gold,” Chilters said. “So I wanted to go work for him.”

“He taught me from the ground up,” Chilters said.

A few years later, court documents state, Reuter’s “ambitions grew.” He moved his operation to Columbia and expanded it to include investment opportunities. He bought a strip mall on Green Meadows Road and formed Green Meadows Properties LLC and Bluff Creek Properties LLC in June 2002. He sold the strip mall on Green Meadows and acquired another on Nifong Boulevard, worth up to $3 million.

It was around this time that Reuter became acquainted with Daryl Miles Brown. In August 2003, Reuter and Brown formed Vertical Group, under which six subsidiaries were formed. Reuter brought with him to the company three-fourths of Liberty’s staff after that company closed in March 2004.

Reuter said in July 2008 in a deposition that he had never checked into Brown’s background.

“He walked the walk, and, I mean, the last time I went to the dentist, I didn’t ask for a copy of his diploma either,” Reuter said, according to a transcript. “He’s a dentist.”

According to the bankruptcy judge’s ruling, Reuter was impressed by Brown’s fantastic stories — stories about his days playing football for the Kansas City Chiefs, about being a highly competent securities salesman hobnobbing with the rich and famous, about being close with Donald Trump’s “people” and Michael Jordan’s “people.” These were stories that Reuter had retold to potential investors as fact but that later proved to be untrue.

One story he passed on to Trom in October 2004, when Trom approached his friend about getting a loan to buy a business, was that Brown had access to both $2 billion in “papers” and a highly profitable trust.

Reuter told Trom that through his association with Brown, he could access a low-risk, high-yield investment program that could net him $5 million as long as Trom was willing to fork over an initial investment of $175,000. He was told the money would be used to acquire “standby letters of credit.”

Reuter said that he and two other investors would even put up $175,000 of their own money and that the money would be forwarded to a “Dr. B,” or Dr. Bichai, a man whom Brown had vouched for but wanted to keep a secret. In addition, because this investment deal was a “special opportunity,” there would be no contracts, according to court documents.

In the three months after Trom wired the money over, he never got his promised payoff. What he did get from Reuter and other officers at the company were excuses: delays resulting from the holiday season, government restrictions on the flow of the euro, Dr. Bichai taking junkets in the Cayman Islands or being too drugged up to sign contracts because of the painkillers he was taking for injuries he received in a car accident — Trom heard it all.

Andrew Ryder, an FBI agent involved with an investigation into Vertical, for which search warrants were issued in March 2005, testified in an affidavit that though he was investigating the company, a loan officer there had looked into “Dr. B” after payments were missed. The officer found that there was a federal indictment against a “Dr. B,” a.k.a. Samuel Bichai of Clearwater, Fla., who was charged with more than 80 counts of fraud.

The officer had told Reuter about the indictments.

In addition, Reuter knew by February 2005 that Dr. B had made off with the money. But Trom would not find out about this until a few months later in May 2005, after more investors were offered a similar deal by Vertical. Reuter then apologized and said he had been duped as well.

Reuter also knew at this point that the Missouri commissioner of securities had conducted an investigation into the company in late 2004.

In his opinion, Judge Dow wrote that Reuter is “financially successful” and “sophisticated,” with a “sharp business acumen.” The judge said that though Reuter lost money on the deal, he did not have the right to be reckless with his neighbor’s money.

Trom said it was more than just recklessness on the part of Reuter that led to the loss of his money.

“It’s so complex and convoluted,” Trom said. “It’s an amazing little scam he pulled.”

“We had Nate’s word…”

The other investors named in the lawsuit against Reuter were offered a slightly different deal from Trom.

Their money would be wired to an escrow account maintained by Dennis Cole, an escrow agent in Florida. There were promises of big returns with no risk.

Cole, who had knowledge that Vertical had been involved in illegitimate practices, cooperated with investigators when he received federal charges for his dealings with Vertical.

Chilters and his fiancée, LaDonna Henderson, needed a loan for a friend to start a convenience store and approached Reuter to help. He told them they would need to front $300,000 to show that their assets were liquid. Then he told them about an investment deal that within one month would return their principal investment, plus $700,000.

On Feb. 1, 2005, Henderson wired the investment to an escrow account in Florida.

Later that month, James Fields of Lenexa, Kan., and an associate were shopping for loans to rehabilitate houses and heard about Vertical from Rick Williams, an officer in the company.

Fields said Williams told him that Reuter could get Fields in with the “movers and shakers” of trading.

In a meeting with Brown, they learned about an investment opportunity with which the company was involved.

When they came back for a subsequent meeting about this opportunity, the plaintiffs said it appeared Reuter was in control of things. He sat at the head of the table, directed the meeting and fielded questions. Fields was also told that it would only be about 30 days before he started seeing returns on his investment.

For Fields, it wasn’t just the deal that sounded pleasing; so did Reuter. He said Reuter talked about his family and told him he was Catholic. He told Fields that he wanted to build a church.

It sounded like such a sure thing that Fields — who, like many of the plaintiffs in the case, had never invested before — put up $50,000.

Like Trom, Fields did not receive the payout he had been expecting on the date he was told he would receive it. When he approached Vertical’s officers about the status of his investment, they offered the retired insurance agent a job managing the company’s insurance portfolio.

But when Fields returned to the company, this time as an employee, things were different. The company’s computers had been confiscated by the FBI, who had already begun investigating Vertical. Brown explained to Fields that it was just a mistake.

Amy House, an accountant for Vertical, told the FBI in May 2005 that Reuter, Brown, Williams and Chuck Bowman, another officer, were known as the “Ivory Tower” of the business and that their meetings together were usually held in secret.

When Fields began to work for the company, he was told that Reuter had resigned.

More red flags were raised for Fields when he began to look into the company’s insurance portfolio. He discovered there wasn’t one.

“There was nothing there,” Fields said. “There was a shell of nothing. Everything was gone.”

Legal troubles for the company began to mount. The Missouri Attorney General’s office filed a lawsuit against the company in May 2005, and Brown was arrested at gunpoint in September 2005 at his Columbia home for federal wire fraud.

Brown is currently serving a 15-year sentence in a federal prison.

Reuter was never arrested for anything to do with Vertical. In his 2008 testimony, he blamed the problems with the investments on Brown. But investors disagree.

Fields said he never would have invested in the company if it weren’t for Reuter. He said he “trusted in Nate.”

“I would not have been taken if it weren’t for Nate,” Fields said.

Chilters, whose fiancée lost the largest amount of money of all the investors involved in the lawsuit, said he trusted Reuter with “his life.”

“We had Nate’s word,” Chilters said.

The investors filed a lawsuit against Reuter in 2006, and in 2007 Reuter lost his representation because the court ruled that his attorneys, who were also acting as counsel for Vertical, could not represent Reuter individually. Thus he could not defend himself against the accusations made in the lawsuit.

Reuter filed for bankruptcy protection, which prevented him from paying the damages that the plaintiffs claimed were owed to them.

Recouping losses

The May 19 decision means a trust fund set up in his wife’s name and his holdings in Bluff Creek Properties and Green Meadows Properties could be liquidated to reimburse investors.

In an April ruling, the judge decided that Reuter is responsible for investors’ losses because Reuter knew that he and other officers in the company were not certified by the Missouri Secretary of State office to trade securities, that Brown had participated in “fraudulent business activities” and because Reuter had already expressed that he had trouble trusting Cole.

The judge wrote that Reuter had misrepresented himself and the company and had worked to create a “false impression of legitimacy, trustworthiness and credibility.”

For the most part, the investors said they are satisfied by the ruling in the bankruptcy court. But they said Reuter got off easy by not getting charged in criminal courts.

Chilters said the punishment should have been harsher.

“When he’s penniless and broke and has no assets, that’s when justice is served,” Chilters said.

According to a transcript of a taped deposition from July 2008, Reuter said he didn’t make any money from Vertical and that the family had a negative cash flow.

He sold his house on Woodbury Court for $400,000 and now works as a self-employed carpenter in Columbia. The bankruptcy ruling indicates that Reuter has no disposable income, receives an allowance from the trust fund and has given no indication that he will seek any more lucrative career opportunities.

Daniels, Reuter’s lawyer, said the case and the ensuing media attention have “ruined” Reuter’s life.

Trom, because of his closeness with Reuter, has been the main point of contact for the news media since the scam made headlines and offered his words in statements released by David Brown, the attorney for the investors. But he said it was a job he would rather not have.

At this point, Trom said, he’s lost the anger he once had over the investment scam.

“Yeah, it pisses me off,” Trom said. “But I don’t sit and stew over it every day.”

Trom, a district sales manager for Trail King, a national distributor of customized semi-trailers used for transporting construction equipment, has been more worried about falling sales numbers from a sagging construction market than the “drawn out process” of trying to recoup his money in the court system.

He said he would even forgive Reuter if he approached him today and “owned up” to his role in the loss of his money.

Reuter has recently tried to recoup some losses of his own in bankruptcy courts. He asked the judge about a rifle he lent Trom before the investment deal. Trom said that got some laughs in the courtroom and said he intends to hold on to the rifle.

“It might be all I ever get,” Trom said.