Skate the Line

- Photos by Ken Mitchell. Team portraits by Sam Surgener.

- "Skate the Line" originally appeared in the August 2024 "Sports" issue of COMO Magazine.

How CoMo Roller Derby went from punk-rock punishers to four-wheeled philanthropists

In the beginning, they were the Destruction Junction Derby Dames, a rough ‘n’ tumble assemblage of ass-kickers dressed in fishnets and facepaint. They later became known as the CoMo Derby Dames and skated under that banner until 2018, when they rebranded to reflect the league’s gender diversity.

But these days, CoMo Roller Derby has a softer side. Oh, the traveling team still gives as good as it gets on the track, but its focus is more on community building and charitable giving than it is bruising and brawling.

Flipping the Script

According to the National Museum of Roller Skating, roller derby dates back to the mid-1930s, when Chicago-based event promoter Leo Seltzer dared to dazzle Depression-era crowds with something a smidge more stirring than the walkathon. The first roller derbies were endurance races during which coed duos tag-teamed 57,000 laps — about 3,000 miles — around a flat track.

To zhuzh up the action, Seltzer and sportswriter Damon Runyon drafted new rules to encourage contact between the skaters. Over the next several decades, it became something like professional wrestling. There were costumes. There were characters. There were storylines and subplots. It was fun, but it was fake.

Then came a woman-led revival in the early 2000s. These aughties-era bouts were scrappy, do-it-yourself endeavors. The skaters put on a show, but they were in it to win it — this time for real.

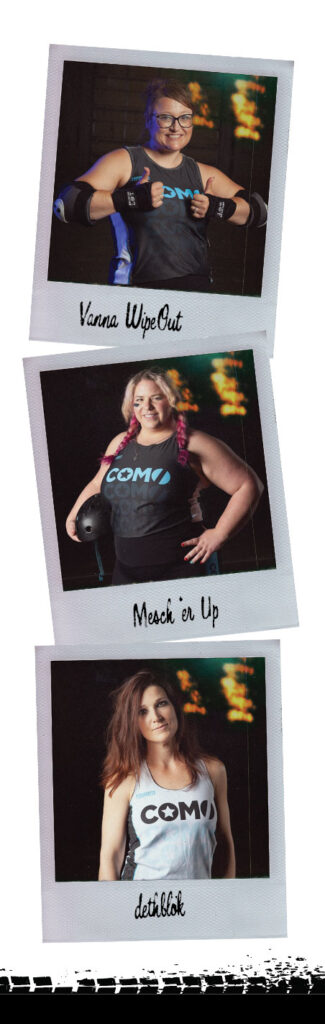

Jennifer Bean, aka dethblök, has been with CoMo Roller Derby since it got off the ground in 2007.

“The first practice was on a Thursday and I was there,” she says. “Since then I’ve gained a group of friends I didn’t know I needed. I have definitely injured myself more in the past seventeen seasons than I would have had I not, but there’s a very famous skater named Bonnie D.Stroier, and she’s credited with saying, ‘Roller derby wrecked my body but saved my soul.’”

How can an activity oft-associated with violence offer salvation? There’s been a bit of an evolution over the years. These days, it’s more about sport than spectacle. The skaters still have their noms de guerre, but they’re more likely to don athletic shorts and a jersey than a miniskirt and deconstructed tank.

“Most of us don’t wear fishnets anymore because if you take a fall, it will embed the fishnets in your skin,” dethblök says. “We call it rink rash.”

Mesch ‘er Up, née Kelsey Mescher, says the early campiness of it all was born of necessity, but it doesn’t necessarily serve the sport anymore.

“There had to be a reason girls were hitting each other on skates, there had to be a bit or a storyline,” Mesch ‘er Up says. “But the decade since I left graduate school, there was the #MeToo movement, the growth of women in sports, the Caitlin Clark effect — it’s more comfortable to own that we play sports.”

It’s not just attitudes toward women’s sports that have changed. dethblök says the Women’s Flat Track Derby Association, or WFTDA, has introduced new rules over the past decade that create a safer environment for athletes.

For example, when dethblök started in 2007, the rules stated that a jam, or point-scoring opportunity, started on one whistle to release the blockers — a defensive pack of four skaters — followed by another whistle to release the jammers — the speedy skaters who score points by lapping the other team’s blockers.

“You have a few cars that are going slow and then you have those cars that are going fast coming up behind you. It was designed for impact,” dethblök says. “We were getting spine injuries, concussions, whiplash. Now, the jam starts on one whistle and everyone goes.”

Today, everyone starts on the same whistle. These new rules don’t just protect players, but also shift the game play to emphasize athleticism versus pure aggression.

A Track of Their Own

One of the biggest challenges CoMo Roller Derby has faced has been a lack of home venue. Currently, the league hosts bouts at the Bob Lemone Building at the Hallsville Fairgrounds.

“We love the Hallsville Community Development Association,” Vanna WipeOut says. “They are very gracious, and we are very grateful for how welcoming they have been of our people and our sport.”

Still, the league would like to be in Columbia, where most of its skaters and fanbase live.

Vanna WipeOut knows they have the potential to draw big crowds. In 2015, the league was able to raise $16,000 — surpassing its goal of $10,000 — to build a floor at the Columbia Canine Sports Center. Its comeback bout brought in a 600-person crowd.

Alas, the space didn’t meet fire codes for crowds that size, so it was back to the drawing board. But the league was undeterred. It had its proof of concept.

“We knew if we got back to CoMo, we could bring fans back,” Vanna Wipeout says.

For the past couple of years, the league has been working with Columbia Parks and Recreation to identify a solution. Members presented one-page testimonies about the potential economic impact of hosting bouts in Columbia.

“People eat and stay in hotel rooms and do all the things that basketball teams and volleyball teams do,” Vanna Wipeout says.

The work has paid off. Current plans for the Sapp Building, which will be built at the Northeast Regional Park, include a dedicated track for roller derby.

The hits are still there, though. dethblök says some leagues like St. Louis’s Arch Rival Roller Derby have a more competitive mindset.

“Their travel team is a bit cut throat. They can chew you out and spit you out,” dethblök says. “That’s not really CoMo’s ethos. We do want to win, but our mission statement is about the empowerment of people through sport. That’s really what we want to do more than anything.”

Putting in the Work

While CoMo Roller Derby is an amateur league, it takes a lot of work to be rink-ready.

dethblök says one of the first things newbies work on, even before they strap into skates, is building ankle strength and mobility. Exercises like heel raises and single-leg balances can help.

“There are stretches that ballerinas do that we use quite a bit of,” dethblök says. “The first thing you do is you trace the alphabet with your foot to activate all those little muscles, all that connective tissue.”

Vanna WipeOut, also known as Jamie Kleinsorge, says there’s a lot of training that happens on and off the track.

“We joke that every season is roller derby season. We practice pretty much year-round,” she says. “We practice at least two times a week, five or six hours. Outside of doing that, I also do a lot of hot yoga. It’s a great core and strength builder. I also do a lot of biking and those sorts of things.”

What’s in a Name?

One of the most delightful aspects of roller derby is the names the skaters come up with.

dethblök named herself after the fictional death metal band Dethklok from the Adult Swim cartoon “Metalocalypse.”

“Dethklok is very silly, sort of like Spinal Tap. They make fun of themselves,” dethblök says.

In the early days of her derby career, she would show up to bouts with zombie makeup and a homemade jersey with her number — “the sign of the beast” — scrawled across the back. It was all in fun, she says, and nobody took it seriously.

Mesch ‘er Up remembers things slightly differently.

“dethblök used to wear a full face up of makeup that made her look like the scariest person on the block. They made T-shirts. Everyone was scary and punk and cool,” she says. “When I joined roller derby, I was scared of everyone.”

When Mesch ‘er Up was looking for a name, she was delighted by teammates’ monikers like Brick James, Felon Ripley, and Maimy Fisher. But she didn’t think something like that would work for her.

“I was super worried that if I picked a name, I wouldn’t turn my head and respond to it,” she says.

As a young soccer player, she’d always gone by her last name: Mescher, which is pronounced “mesk-er.”

“But nobody has ever pronounced my name correctly my entire life. People would check me in and say ‘mesh-er,’ so I became ‘Mesch’ pretty quick.”

A teammate suggested “Mesch ‘er Up” while skating by one day. It stuck.

Vanna WipeOut gets her name from what she calls her 15 minutes of fame: an appearance on Wheel of Fortune during which she advanced to the final round and won $114,700.

“I thought a lot about the Wheels of Misfortune, but someone else had it,” Vanna Wipeout says.

Although she used to wear shorts with “BANKRUPT” scrawled across the back, Vanna WipeOut says the persona isn’t as much of a factor as it might have been at one point.

“I think when I started in 2011, roller derby was still very much seen as staged entertainment. We tried really hard to disassociate ourselves from that,” she says. “When we go out there, it’s real hits and real falls. I think because of that, I have shifted more toward a sports mentality. I don’t really have a lot of flare.”

Community and Connection

In its mission statement, CoMo Roller Derby — an IRS-recgnized 501(c)(3) nonprofit — declares itself a skater-owned and operated league that strives for diversity in membership and strongly encourages community engagement.

To that end, the league is highly visible in the local nonprofit scene. It typically holds two to three fundraisers a year for organizations that are in alignment with its mission and its members’ passions. So far this year, they’ve raised $157 for The Center Project, $453 for Unchained Melodies, and $250 for City of Refuge.

Camaron Nielsen, who serves on the board of directors at The Center Project, says it’s not just the financial contributions that are meaningful. The Center Project, she explains, does offer support and services to the LGBQTIA+ community for the wider Mid-Missouri area, but many outside of Columbia haven’t heard of it. When CoMo Roller Derby holds raffles or dedicates proceeds from concessions to The Center Project during its bouts, people from other parts of the region are able to learn about its mission.

“It’s cool to be able to use those partnerships for visibility for both organizations, Nielsen says. “CoMo has been an awesome partner of ours.”

CoMo Roller Derby also shows up to support other organizations’ fundraisers and events. They might skate in a Pride parade or take shifts at the Food Bank for Central & Northeast Missouri. dethblök jokes — but she’s not really joking — that if a request came in for the skaters to cheer at a child’s tee-ball game, they’d be there.

“When we’re out there and visible, we’re serving,” dethblök says. “It’s like that maturation of punk rock. The most anarchist thing I can do is be kind.”

You Get What You Give

When the skaters talk about roller derby, it’s clearly more than a hobby. They value their connections within the community as well as their bonds with one another and the avenues they’ve been afforded for personal growth.

dethblök says learning to skate through challenges has taught that she’s capable of so much.

“I’m halfway through my life and finishing my PhD,” she says. “I’m going to school, working full-time, and raising a 16-year-old son. I can do hard things. It’s going to suck sometimes, but I can do it.”

For Vanna WipeOut, serving on leadership committees for CoMo Roller Derby has provided valuable professional experience she can tap into as assistant director and senior project coordinator at the University of Missouri’s Center for Applied Research and Engagement Systems (CARES).

“We’ve had The Year of The Receipts and The Year of The SOPs,” Vanna WipeOut says. “That has provided me with a lot of leadership opportunities. I think a lot of the reasons I am where I am today in my job and in my life is because I’ve had the opportunity to be a leader and have strong leaders around me.”

Mesch ‘er Up is quick to point out that showing up to a first practice doesn’t mean someone gets a gang of instant besties. Newbies must put in the time and show their commitment to the league. But when they do, the sense of community is awesome. Her voice cracks as she shares a story about the time her fellow skaters stepped up for her when her father fell ill in 2015.

“My dad had a heart attack and I posted on our group chat on Facebook and I said, ‘Hey, I’m in the hospital. Does anyone have recommendations on heart people in Columbia?’” Mesch ‘er Up says. “Then in 30 minutes, I had two teammates in the waiting room with me, and they had brought me stuff.”

During the six-week period Mesch’er Up’s father was in the hospital, there was a tournament in Indianapolis. Mesch’er Up’s mother — who has since joined the league as a penalty timer and goes by the name Mama Mesch — encouraged her to travel with the team to get a break from the situation on the homefront. On the road, the team showed its solidarity with Mesch’er Up.

“Everyone got red ribbons and put them on their helmets,” Mesch ‘er Up says.

When her father died, the team was there again, this time with gift baskets and a meal train and, perhaps most importantly, a steady presence.

“A couple people just really kept me going,” Mesch ‘er Up says. “Brick James, she’s retired now, but she’s still one of my best friends for life. She had lost her dad as well. She’s a retired teacher and taught me to sew and all these things. Conversations with her got me through it.”

It was also conversations with Brick James that encouraged Mesch ‘er Up to give substitute teaching a try. It turned out she enjoyed the classroom. Today, she is a physics and chemistry teacher at Battle High School and the head wrestling coach.

“Roller derby really is my saving grace. I genuinely don’t know who I’d be or where I’d be,” Mesch ‘er Up says. “I give everything to them because they gave everything to me.”