Missouri’s most dangerous jobs

For most people, the most dangerous part of the workday is the drive in. But for people who work in Missouri’s three most dangerous professions, continuous risk is just part of the job.

Missouri’s #1 Most Dangerous Jobs

Missouri’s #1 Most Dangerous Jobs

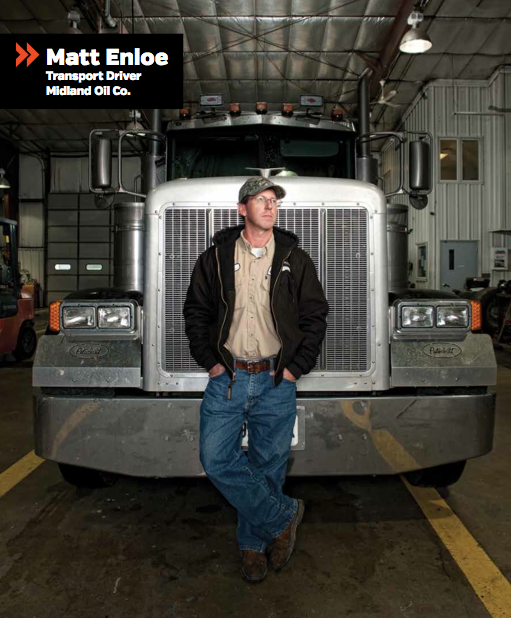

On an average summer day in 2014, a pickup truck stopped dead in front of Matt Enloe on I-35 in Kansas City to let a four-door sedan merge onto the highway. With 80,000 pounds riding behind him in his trailer, Enloe looked for somewhere to go on the crowded highway before making a quick maneuver to change lanes.

What had intended to be a polite act on behalf of the pickup truck nearly caused what would have likely been a fatal accident. But for Enloe, a transport driver for Midland Oil Co. out of Jefferson City, that’s just the most recent in a string of dangers he regularly encounters on the job.

He’s been driving for Midland for almost 16 years and driving in general for nearly 20. Enloe faces a series of daily challenges in the form of difficult road conditions and lack of awareness from the general public.

“The general public often sees a large gap between us and the car ahead of us, whether that’s on the interstate or in the city, and they think there’s enough room for them,” he says. “But that decreases our following distance.”

The one-one thousand, two-one thousand rule taught in driver’s education is much different for trucks the size of Enloe’s. He usually maintains three truck lengths between him and the car ahead — or four or five, depending on conditions including weather and speed.

The most dangerous spot, locally, for truck drivers is the downhill when heading north on the 70-63 interchange.

“With the stoplight and the hill, our time to stop can be pretty short,” he says. The best he can do to mitigate risk is try to predict what cars around him might do and be preventive. With blind spots on both sides of and directly behind his truck, keeping track of all the surrounding cars is not always easy.

What would really help keep drivers such as Enloe safe in Missouri is simple: “We’re bigger and slower, and we need more space.”

Missouri’s #2 Most Dangerous Job

Missouri’s #2 Most Dangerous Job

“Watch and learn.”

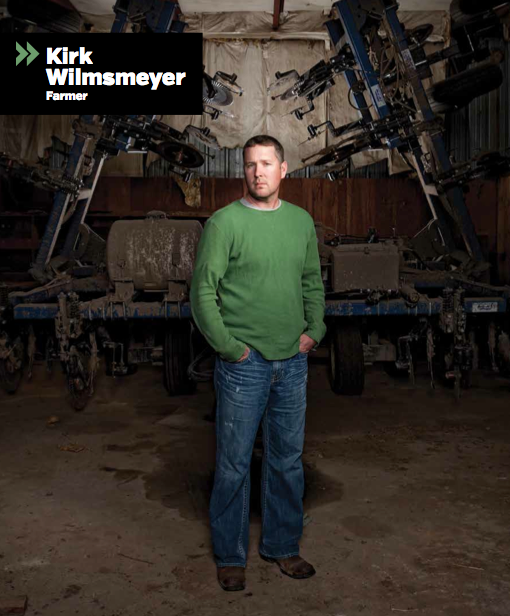

That’s farmer Kirk Wilmsmeyer’s advice to stay safe on the job. Wilmsmeyer learned by watching his father, and those are lessons he hopes to one day teach his two young sons.

“To me, the riskiest part of what we do is either working with cattle or operating heavy machinery,” he says.

“Just having experience around cattle is the best way to stay safe,” he says. “You’ll know their tendencies. … You’ll get a sense of what they might do.” Besides watching from the sidelines, Wilmsmeyer thinks it’s best to start with the easy tasks.

Technology has made the farming industry much safer (and more efficient, but that’s a conversation for another day). For example, a combine won’t continue running without someone in the driver’s seat.

“There are a lot of old farmers missing a finger or two because they tried to fix their tractor while it was running,” he says.

His closest calls have been working with cattle and getting a tractor too close to a ditch, where it might roll — and one instance when he almost lost a finger in a baler — but he’s never thought of farming as a very risky job.

“Honestly, it gets safer year after year,” he says. “It gets harder and harder to get hurt on the job.”

Missouri’s #3 Most Dangerous Jobs

Missouri’s #3 Most Dangerous Jobs

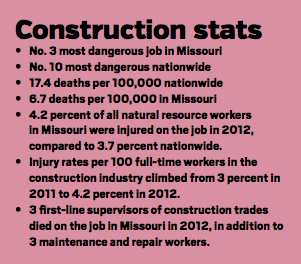

Like most small-business owners, Connie Leipard wears a lot of hats. As co-owner of Quality Drywall Construction with her husband, Mike, she does the accounting and payroll as well as supervises project managers.

She’s also the company’s safety director. Construction is the third most dangerous industry in Missouri, and it’s her job to make sure everyone gets the training they need to stay safe on the job. Quality Drywall Construction has 35 employees and is often working on five to seven projects at any given time.

A few years ago, her company began monthly safety meetings to discuss onsite safety procedures and general health issues, including some of the musculoskeletal issues that often plague drywallers. They also train on general safety issues, such as cleanup procedures, how to handle allergic reactions to supplies and handling the heat of summer.

Initially, it was difficult to change industry veterans with 20-plus years of bad habits, but the consistent training has paid off. The company has had no major accidents on the job, though they have been at sites where someone from another subcontracting team has been severely injured or even lost their lives.

Although some general contractors have daily “toolbox talks,” as Leipard calls them, to talk about the day’s workflow and safety issues, if that isn’t the case, it’s up to Leipard’s foreman.

“You have to watch what everyone else on the jobsite is doing, not just your guys,” Leipard says. For example, if one of the drywallers is on stilts, as they often are, and another team hasn’t cleaned up its area, they might step on something and fall. Each site is different, though, and safety procedures will usually be outlined in the contract.

“Some companies are more tuned in to safety than others, but I think it’s becoming more common for everyone to be on board in making sure safety is a top priority,” she says.

The Nation’s #1 Most Dangerous Job

With more than 30 years in the nation’s most dangerous jobs, it’s no surprise that Warren Gerlt of Fayette was nominated as 2014 Logger of the Year based on the quality of his work and commitment to safety procedures.

Although, he has had some close calls while harvesting white and red oak, walnut and palette-type trees in mid-Missouri. In one instance, he hadn’t paid attention to the vines hanging from a big tree he was harvesting, and the vines pulled down another tree within arm’s reach.

Another more complicated instance, Gerlt can sum up in one sentence: “Never trust a hanging tree.”

When Gerlt fells a tree, he uses an open-face notch. “That eliminates a lot of the safety hazards and allows you to drop that tree right where you want it,” he says. It’s one of the many standards of safety be learned through a Professional Timber Harvester class, required for all foresters. Gerlt completed his in 1999, and his son and another of his employees just completed their PTH training in October.

He says a top priority is knowing your saw. “At 1200 rpm, you have to follow safety procedures,” he says. Another important element is to eliminate spring poles, or small trees that might be unpredictably brought down by the larger tree you’re harvesting.

“The biggest thing is being aware of your surroundings.”

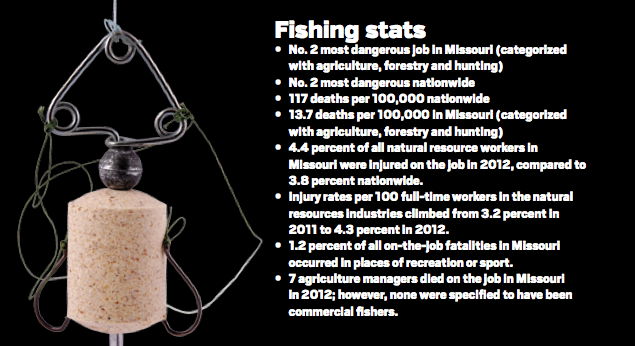

The Nation’s #2 Most Dangerous Job

Commercial fishing in Missouri is allowed on the Missouri River, Mississippi River and parts of the St. Francis that border Arkansas. In fiscal year 2014, which began in July, more than 160 commercial fishing permits have been granted statewide, according to Joe McMullen with the Missouri Department of Conservation. That number, which McMullen expects to be similar to previous years, will continue to grow through June of 2015. Additionally, there are three active commercial permits for the harvest of caviar in Missouri.

The number of permits, McMullen says, tends to grow proportionally to market prices. Regulations might also be a factor in the number of permits. For rivers that border other states, if a fisher finds it advantageous to get a permit from the bordering state, he or she can do so. Weather, however, has a greater impact on the overall harvest rather than the number of permits granted.

“For example, in a flood year, that would certainly impact [the amount] because it’s keeping them off the river,” McMullen says.

Commercial permits are granted to individuals, though they may have an assistant who only requires a regular fishing permit.

“For example, if you had a fish market, you could reach out to three or four [commercial fishers] to keep your market stocked, but each of those individuals would need a separate license,” McMullen says.

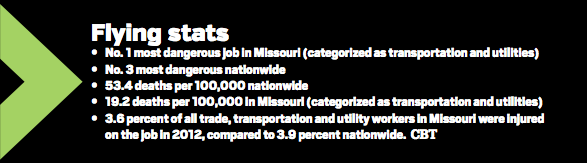

The Nation’s #3 Most Dangerous Job

It turns out being a pilot is as complicated as it sounds. According to Randy Clark with Central Missouri Aviation, there are many categories of pilots: recreational pilots, private pilots, commercial pilots, corporate pilots, airline pilots and more.

Clark says some categories are riskier than others, such as aerial applicators (crop dusters). Although there aren’t many around here, Clark says, they are “plentiful down in the Missouri Bootheel.”

Another area of flight that Clark says bears risk is Life Flight, or air ambulance, helicopters. Although Boone Hospital accepts helicopter transfers, it doesn’t own a helicopter or employ pilots, according to Ben Cornelius, the hospital’s manager of marketing and communications. University of Missouri Health Care also doesn’t own its own helicopters or employ its own pilots. Rather, it provides medical staff and direction for the Staff for Life Helicopter Service, which utilizes three helicopters, at Osage Beach, LaMonte and University Hospital, according to Jeff Hoelscher with MU Health Care.

Flight engineers, also categorized with pilots by the BLS, are “becoming a thing of the past,” according to Clark. “The days of flight engineers — part of a three-man crew in the cockpit — with the airlines are history.” Since 2004, the total number of flight engineers in the U.S. has decreased by nearly a quarter.

Above all, Clark reiterates, the key to aviation is safety, “through training, flight currency, awareness of weather and potential hazards to flight and not exceeding your personal or professional capability.”