Vani$hing Act

No company is immune to the occasional sideways employee, siphoning corporate funds. But stories of some of Boone County’s most successful embezzlement schemes shed some light on the situation.

No company is immune to the occasional sideways employee, siphoning corporate funds. But stories of some of Boone County’s most successful embezzlement schemes shed some light on the situation.

TRACI BUSENBARK BEST knows a lot about embezzlement prevention. She should; she’s been stung by this crime not once but twice.

No matter what the amount of the loss — from the $26,000 syphoned out of Busenbark Flooring and Granite to the $400,000 in question at the Missouri State University bookstore or the $1.1 million at U.S. Bank — the cause is the same: a trusted employee who finds a way to short-circuit the firm’s checks and balances.

Today, Busenbark Best says she’s better for the experiences. She’s tightened up her office procedures and now has embezzlement prevention practices in place, including the most important one: “You need to have a double set of eyes on everything,” says Bill Ratliff, executive vice president of the Missouri Bankers Association.

Keep an eye on the ball

When Busenbark Best was hit the first time, her business was expanding, and she simply became too busy to review everything. “My eye wasn’t on the ball,” she says. “I was trying to juggle too many things.” She let one employee manage the books from start to finish: another key mistake.

In Busenbark Best’s case, the first embezzlement involved an employee taking cash and then either entering a discounted amount of cash or not entering the income at all and pocketing the money. The second case involved an employee who opened a credit card in Busenbark Best’s name and then bought items for her own use. This employee opened the mail and paid the bills, which kept the crime from being discovered. Busenbark Best did not discover her crime immediately, and the employee died before she could be prosecuted.

Busenbark Best now has divided the accounting practices and makes sure she oversees the mail and deposits.

Oversight of the person doing the accounting is crucial, says Ryan Haigh, Boone County assistant prosecutor attorney. “As far as I’ve seen, the person responsible for the books is most often the person embezzling money.” The key to prevention, say other experts, is conducting regular internal and external audits.

Slips in security often take place in smaller organizations or when that task falls to a member of the board of directors. “Someone’s supposed to check, but nobody does,” Haigh says. Several of the organizations stung by embezzlement are small firms or nonprofits such as the Mid-Missouri Chapter of the Alzheimer’s Association, which had $96,000 taken in 2006.

But like all business people hit by embezzlement, Busenbark Best had trusted her employees.

That trust is the key to all embezzlement. David M. Ketchmark, acting U.S. attorney at the U.S. Attorney’s Office, Western Division, has heard it too many times: “But they were a trusted family friend.”

That was the case for Busenbark-

Best the first time. She’d known that employee since she was a child. The second time, the person who later betrayed her was the person who uncovered the first crime, which led Busenbark Best to think she could be trusted.

Theft prevention and red flags

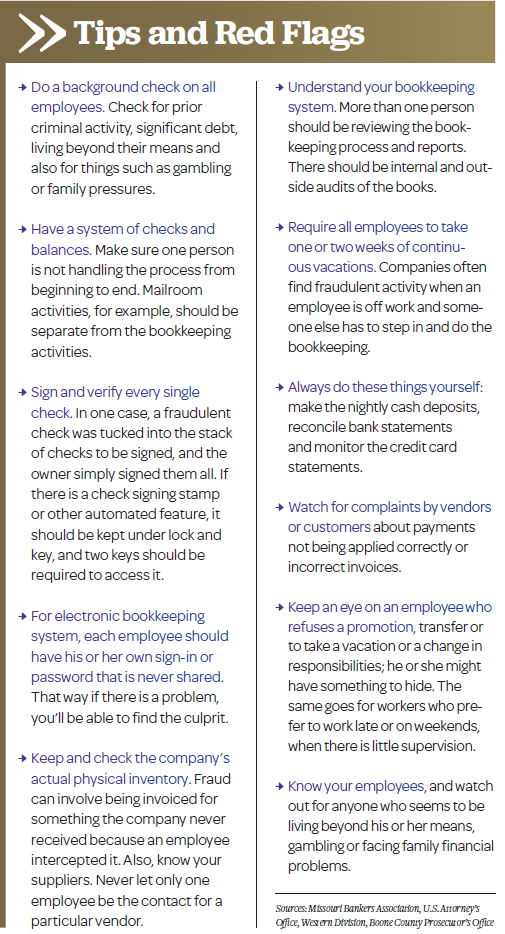

Background checks should include looking for past criminal behavior as well as credit record and lifestyle issues, according to Ketchmark. “You don’t want a frequent [customer] at the casinos,” he says, citing a case of an embezzlement of $971,000, all of which the accused gambled away. Other red flags can include someone living beyond their means or even working late and weekends when they’re unlikely to be supervised.

In a 1995 case of a $50,000 loss to Boone County, a co-worker noted in a newspaper article that she’d been grateful to the employee who always did more than she was asked. That crime, the newspaper report noted, went on for two years.

Theft prevention should include requiring employees to take one or two weeks of continuous vacation so companies can catch this kind of crime, Ketchmark says. Embezzlement is often discovered when an employee is unexpectedly away from his or her job and another person has to take over. That’s how Busenbark Best discovered both crimes at her firm; the employees were away, and the irregularities surfaced.

Other red flags include a worker who is resentful or feels underpaid and suddenly stops complaining. “They might be supplementing their income with your funds,” Ketchmark says. Employees who refuse a promotion or a transfer should be watched, too. A new job or promotion, Ketchmark says, isn’t as lucrative as taking your funds.

Busenbark Best says her bookkeeper had been resisting any change in the office, including easing her workload. “She didn’t want to let go of that responsibility,” Busenbark Best says.

Even before the crime was uncovered, though, Busenbark Best says she’d suspected something was wrong. In the first case, despite doing good business, the firm never seemed to have any cash on hand. But she told herself that was normal growing pains for a company. Also, each time she noticed the meager funds, the employee suddenly became difficult and confrontational, something she attributes to their guilt and stress at the time.

That’s the last embezzlement prevention tip Ketchmark offers: “If your gut tells you something’s wrong, act on it.”

As for Busenbark Best, she’s philosophical and practical about it: “If a thief wants to be a thief, they’ll find a way, but I’m in charge of my books now, I’m reconciling them, and I’m going over the bank statement. I’ve put in some stop guards, and I look at my deposits every day.”