EPA-ordered Hinkson cleanup off to slow start

Time Keeps Ticking

After the EPA issued its final polution-control plan for the Hinkson Creek, proposed projects for reducing stormwater flow are off to a slow start.

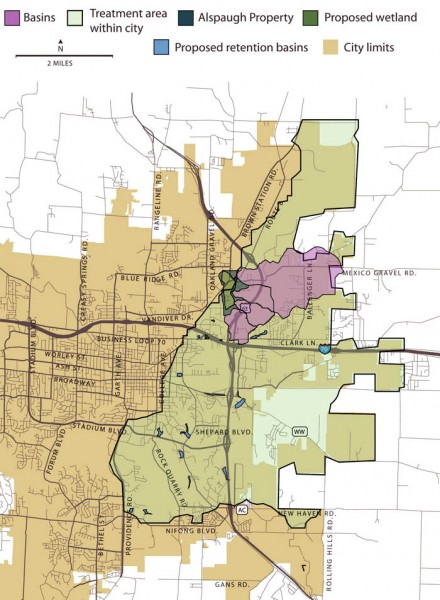

Public Works Director John Glascock’s presentation to City Council was packed with proposed projects for reducing stormwater flowing into Hinkson Creek and came just a month after the Environmental Protection Agency issued its final pollution-control plan.

The projects included more than a dozen retention basins in the watershed, along with small dams and reservoirs and a large wetland in the upper portion of the creek’s meandering path through the city. Asked what it would cost to buy the major portion of the land for the proposed wetland, Glascock said $3 million to $5 million.

That last part was news to John Alspaugh, the landowner, who happened to be at the hearing for another matter related to new sewer lines that will be running across his 200-acre farm that flanks Hinkson Creek.

Glascock acknowledged that no plans have been made to acquire any of the property shown in maps he presented in February but added that he was doing what the Council wanted. “The Council basically asked, ‘Knowing what you know today, where would you start?’” he said. “And that’s basically what we came up with. We would like to do the monitoring before we do anything like that. … We don’t want to be buying things we don’t need to buy.”

Glascock was referring to the EPA’s recommendation that the city monitor and assess the water quality in Hinkson Creek, one of the sticking points in the negotiations between federal and state regulators and the three parties in the court-ordered creek cleanup: the city, Boone County and MU.

The county and university are considering whether to join the city in its plan to appeal two aspects of the regulations known as a TMDL, or Total Maximum Daily Load: The first is a percentage related to aquatic life, and the second is the deadline for implementing the EPA plan: three to five years.

The county, meanwhile, is already taking the first steps to reducing stormwater runoff. Using a recent three-year, $713,000 grant from the Department of Natural Resources, the county is partnering with the city and Missouri River Communities Network to begin implementing stormwater “best management practices.”

With the funding, Bowman said, the county will do some water-quality monitoring, implement BMPs at Sunrise Estates subdivision and create a subwatershed at Grindstone Creek, which flows into the Hinkson.

Glascock pointed out during his work-session presentation that the city had no money allocated to the projects. City officials have estimated that implementing the TMDL could cost more than $100 million.

But even if the city had the money, Alspaugh said he wouldn’t sell his property so the city could turn it into a wetland that slows the flow of water into the Hinkson.

The Alspaugh Creek Bottom

“What would I do with $5 million dollars?” Alspaugh, a retired MU professor, asked, as if the answer were as pat as what he ate for breakfast.

Flanked by Scotch pine trees he’s planted over the years, Alspaugh said he’s not interested in selling the land he’s owned for about 30 years. And even if he were willing to sell, Alspaugh said it doesn’t make any sense for the city to turn it into a water retention basin.

“The truth of the matter is water does not run uphill,” he said of his elevated property. “And I don’t know how you get the water out of Hinkson Creek beyond to the farm, except when it’s flash flooding.” He said it makes more sense for the city to build a dam across Hinkson Creek by the landfill, which the city already owns.

“On the other hand, they don’t want to do something that requires maintenance, and I don’t know how they’re going to do anything of any significance that doesn’t require maintenance,” Alspaugh said.

Two subdivisions have been built near Alspaugh’s property, which adds to the industrial development upstream, he said. Rather than slowly percolating into the soil, rainwater flows off roofs, parking lots, roads and lawns and increases the direct flow into the creek. That, Alspaugh said, has caused the Hinkson to widen significantly and tear down bordering trees.

Alspaugh, a statistician who still teaches one course at the university, said he spent 10 to 12 hours reading the Hinkson Creek TMDL. He was impressed with the data presentation and came to understand how the EPA came up with the requirement that the city, county and MU reduce stormwater flow into the Hinkson by 40 percent.

Jason Hubbart, an MU hydrologist leading a team of scientists developing a monitoring project for the Hinkson’s entire watershed, explained it in lay terms: “The idea is, since we don’t know what the pollutants are, we’re going to just shut down the valve so that less pollutants are theoretically being transported. That (reduction) figure was estimated from examining rainfall runoff relationships in other watersheds.”

Alspaugh brought the issue down to concrete terms: “We’re going to have to do something about all the flash flooding from all the rooftops and the buildings, and I should tell you that the flash flooding is a lot worse at our place now than it used to be. There’s 3M and Square D and Columbia Foods, and there’s all kinds of runoff from the industrial development on Route B that comes down Hinkson Creek.”

Monitoring creek water

Glascock said the first step, the first phase of implementing the TMDL, is to assess what he referred to as the creek’s biocommunity.

The water monitoring must be done, he said, “in the spring and the fall, and, of course, by the time we’d have a contract, spring will be over. Somewhere around the spring of ’13, we hope to have enough data to make some determinations.”

Until the monitoring is well underway and funding is secured, the city will do “probably nothing” in regard to major projects designed to improve the health of the creek, Glascock said.

Midkiff, conservation chair of Sierra Club’s Osage Group, questioned the city’s motives because the data already exists. Midkiff said he received Hinkson water-quality data through 2010 for free from Susan Higgins at Missouri Department of Natural Resources.

“I think they’re going to be shopping for a firm that will give them better data that shows that Hinkson Creek is not impaired,” he said of city officials. “I think they’re going to be data shopping.

Midkiff said there are a number of certified and qualified stream teams along Hinkson Creek. “I think $100,000 that Glascock is willing to set aside for macroinvertebrate monitoring is just throwing away taxpayers’ money because the stream teams do that voluntarily at no charge.”

When asked why the city, county and MU aren’t using stream team data to guide their cleanup efforts, Bowman said some of the data can be used, but most of it isn’t specific enough.

“Remember science (class) when you had to go down to genus species?” she asked rhetorically. “The stream team data for the most part goes to family, so we’re paying someone to take that down to genus species. By doing that, we get a much clearer idea of how many invertebrates are in each category, whether they’re tolerant of pollution or whether they’re not tolerant.”

And what about Hubbart’s study? In 2008, with $2 million in federal grants, Hubbart and a team of graduate students began gathering water-quality data at five different stations along the stream. The remaining funds will keep the project going for about two more years, according to Hubbart.

After the final TMDL plan came out in January, the city contacted him about potentially partnering on the project, Hubbart said, and in March he sent the city an official proposal.

“If they partner with me, then they’re going to get access to those data, and we’ll work together to monitor Hinkson Creek over time,” Hubbart said, “so we can actually quantify the results of changes in development practices.”

What would stormwater reductions cost?

Steve Hunt, Columbia’s environmental services manager, said a study funded through a federal Clean Water Act grant identified 20 stormwater “hot spots” between Interstate 70 and Broadway. The study performed by The Civil Group estimated that it would cost $1.1 million to reduce stormwater flow from all of the hot spots, and that doesn’t include the cost of buying land.

The city estimates that it would cost $100,000 a year to have specialists monitor the creek’s water quality.

In the February work session, Glascock said the goal is to restore the floodplain and natural cover to the watershed, but the Council would have to pass an ordinance restricting floodplain development. Restoring natural cover is costly upfront, Glascock said, but cheaper in the long run compared to engineering structures that have high maintenance costs. “We want to do it as naturally as possible,” he said.

The ability to put any plans in motion hinges on whether citizens approve a stormwater utility rate increase in August. Glascock said he won’t know the amount of the proposed increase until he meets with City Council on April 13.

If the utility revenue is increased, the first actions would be to create water retention basins on city-owned properties, Glascock said. “You could do something at Twin Lakes; you could do something, along Stephens Park … possibly even in Lions Park,” he said. “We could do things at the landfill, those kind of places to start with.”

“If (people) don’t want to help pay to clean it up, then they should support the people that regulate the development and keep the pollution out of the stream in the first place,” he said. “It’s up to the people of Columbia to decide what type of community they want to live in.”

Midkiff said he’s not sure a utility increase is necessary, especially with so many effective, low-cost, low-tech ways for the city and its citizens to reduce stormwater runoff.

If 1,000 people each built a rain garden, the city could realize about the same amount of stormwater reduction as the city’s proposed $300 million plan,

he said.

The city helped to create some of the stormwater problems by letting contractors for developments such as the Walmart Supercenter on Grindstone build huge impervious parking lots, he added.

“The Walmart Supercenter (has) an enormous paved parking lot,” he said. “And they could just go out and cut some holes in the parking lot and let the rainwater seep into the gravel under the parking lot rather than running off immediately into Hinkson Creek.”

Ikerd doesn’t see the issue as quite so cut and dry. “I think what we’re dealing with here is a very complex system, a natural ecosystem, which a watershed is,” he said. “You can’t take it apart piece by piece like a machine and say, ‘Well, this is this faulty part, and we’re going to replace that part, and then the whole thing will be fixed.’ It’s all interrelated.”

Hubbart said he agrees with the city’s decision to appeal the TMDL’s five-year implementation requirement, which he called “pretty unlikely.”

Bowman, the stormwater coordinator, said the county supports the city’s appeal of the TMDL timeline and requirement that all samples adhere to the prescribed water-quality level 100 percent of time.

“We have talked to other communities around the country,” she said. “San Diego has numerous TMDLs in their watershed, and they have a 20-year implementation schedule rather. That’s much more realistic, and so that’s what we’ll be pushing for — something on that level, 20 to 30 years.”

The Missouri Department of Natural Resources, which is the EPA’s implementation arm, is flexible about the deadlines, Renee Bungart, the deputy communications director, said.

“Implementation of TMDLs is a long-term process; there’s no set time frame,” she said. “There’s nothing that says, ‘This has to be finished and improved and finished by X date.’ It doesn’t work that way.”

On the timing issue, Midkiff gave some ground: “Hinkson Creek didn’t get polluted overnight; it’s not going to get unpolluted overnight either.”

This story was funded in part by the community at Spot.Us, a nonprofit news operation that supports independent journalism.