Miscanthus: More than a mere decoration

Ornamental grass increasingly targeted as biofuel source

Ornamental grass increasingly targeted as biofuel source

Professor Stephen Long has been studying Miscanthus Giganteus for the better part of three decades.

The University of Illinois crop scientist began investigating the plant for use as a biofuel in Europe and performed research for universities there as well as the European Union before moving to Illinois in 1999.

Although European countries such as the United Kingdom backed miscanthus research, and Denmark began growing it and using it as a biofuel, the United States seemed more interested in studying a similar plant — switchgrass. Long compared switchgrass, a native North American plant, with Miscanthus Giganteus, originally from Asia.

“It appears to be about the most productive plant we can find,” Long said.

To produce a biofuel that can compete in the marketplace with traditional fossil fuels, you need lots of it, and miscanthus fits the bill. The high yield of miscanthus is only one of its pros. Unlike modified switchgrass, miscanthus is not a native of North America, so its pollen won’t be able to mix with native prairie plants, Long said.

“This will be much more like maize or soybeans; it’s not related to anything here,” he said. “So its genes are not going to get into anything. And it’s sterile, so it can’t spread by seed.”

Miscanthus Giganteus is a naturally occurring hybrid, which makes it sterile, Long said. It was collected in Japan and brought to the United Kingdom and Denmark in the early 1900s for use as an ornamental grass. It likely made its way to US botanical gardens in the ’60s, he said.

But in the past 10 to 15 years, European companies and governments began to use it as fuel for power generation. A number of smaller commercial ventures have been set up to grow and supply the plant for power generation in Europe, Long said. And recently, the Drax B power station in Yorkshire, England, the largest power plant in Western Europe, has begun a conversion to run on 50 percent biomass, of which miscanthus will be a major feedstock, he said.

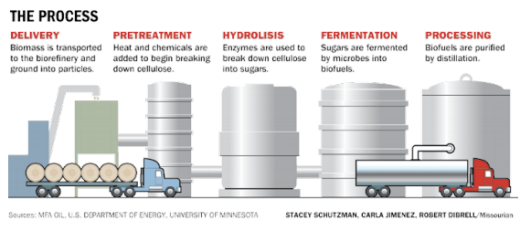

Miscanthus’ use in Europe and its high yield is what attracted MFA Oil, which formed MFA Oil Biomass LLC with Aloterra Energy last month, to begin planting the crop in Missouri and Arkansas for use as an energy feedstock.

MFA Oil President and CEO Jerry Taylor said Miscanthus Giganteus was the “leading candidate” for biomass and is projecting about 12 to 15 tons per acre of yield. The company has a 2-year-old field in Kansas that it is harvesting right now. Although the plant takes three years to produce a mature crop, Taylor said he has liked what he has seen so far.

“We feel pretty good about our projections and that our model is correct, that we’ll get the right tonnage,” Taylor said.

The high yields could even improve, Long said.

“This is basically a wild plant that we’ve kind of propagated,” he said. “So we figure if we start applying breeding techniques to it, we should be able to get even higher yields.”

MFA Oil Biomass’s plans call for growing the miscanthus mostly on “marginal,” or underutilized land.

“We don’t want to get in the food for fuel battle,” said Jared Wilmes, MFA Oil’s biomass project coordinator. “We’d prefer to stay out of that. We think there’s plenty of ground out there that this would fit nicely on.”

And the science so far backs that up. Long said the university has set up 16 sites around the country to definitively answer how well the plant grows on different types of soil. But so far, it seems to do well on soil not well suited for crop production.

“We’ve been able to establish it on different soils, difficult soils,” Long said. “In fact, in Illinois we find our highest yields in the south, and yet our best soils are really in the central and north.”

So far, he and other researchers suspect that has to do with the slightly warmer, slightly rainier climate, which bodes well for Missouri. But he added that the question will be how much miscanthus’ high yields can hold up in the slightly dryer western part of the state. Although it’s efficient in its water use, a much bigger plant means it could need much more water.

“You’re getting 60 percent more biomass, so you may need as much as 60 percent more water,” he said.

The other issue is getting the crop established that first year. Because it is sterile, it can’t be planted using seeds. Instead, its rhizomes — pieces of its stem that grow underground — must be planted.

“Compared to many seeded crops, it’s a lot more expensive to establish,” said Tom Voigt, a professor of crop sciences who also studies Miscanthus Giganteus at the University of Illinois.

Plus, it hasn’t been in commercial production in this country, so the rhizomes are still relatively expensive, according to Long and Voigt. But ever since the first trials comparing miscanthus to switchgrass were completed in 2004, interest has been building, Long said.

Some companies are looking to get into the new market miscanthus could create, Voigt said.

“There’s a huge amount of interest in the country,” Voigt said. “There are a couple of companies that are just starting to ramp up (miscanthus rhizome) production.”

Although the startup costs may be high, Miscanthus Giganteus is a perennial that can last 20 years, so with a long enough time horizon, farmers can make their money back, Long said. But Long admitted that no one is quite sure how long it will last. Stands in Asia could be centuries old, he said, and some are still growing in Europe.

“There are stands in Europe that were planted now over 20 years ago with no or little yield loss,” he said.

The plant’s potential as an easily grown, high-yielding, carbon neutral biofuel isn’t its only benefit. Miscanthus puts a high percentage of its nutrients into its large root system underground. After five years on one of his Illinois plots, Long found that miscanthus puts about 15 tons of biomass per acre underground — carbon it had taken out of the air. That root system is attractive to farmers looking for a plant to revitalize overworked soils.

“Some of the corn and soybean farmers in Illinois are interested in putting this on their poorer acres for maybe about 10 years to try and restore soil carbon levels and then going back to corn and soy,” he said.

That’s one of the main reasons Ronnie Felten, a member of MFA Oil’s board of directors, plans to grow the miscanthus on his Pilot Grove farm. And farmers ready to retire could grow this on land rather than renting it out to someone who might ruin the soil by planting crops on it, he said.

“I hope the next generation appreciates me trying to save the soils out here,” Felten said. “If I don’t take care of it, I sure can’t hand anything off to the next generation.”