Green Jobs: Conservation push energizes Columbia economy

September 3, 2010

Take Tracy Banning and her husband, Trevor Banning. Tracy said the city’s energy saving program compelled them to open their own business, Enhanced Energy Solutions, 12 months ago, which she especially likes because it gives them an opportunity to help people.

The Bannings are among the roughly 45 people who have jobs thanks to Columbia Water and Light’s Home Performance with Energy Star. Enhanced Energy Solutions is among a handful of new companies that perform the energy audits required by the program.

More than 750 residents have taken advantage of Home Performance with Energy Star since the program started in 2008, according to city records. Incentives include rebates and low-cost loans to homeowners who make improvements in their home to reduce energy usage, and that’s on top of state and federal tax breaks. Participants must also get a follow-up energy audit to ensure the changes were made before any payment is made to the homeowners, but the cost of the energy audits is covered by the rebates.

Yet, these numbers only reflect the people directly affected by the city program. They don’t reflect those employed through the ripple effect, said Connie Kacprowicz, utilities services specialist at the city-owned utility.

City figures show each program participant has received an average incentive from the city of $800 but spent roughly $7,500 on energy improvements. The result is $5.6 million that flowed into Columbia’s economy via the Home Performance with Energy Star program.

There’s potential for much more. The city has roughly 45,000 customers.

How it works

The idea behind Home Performance is that it’s expensive for the city to increase its energy supply by buying or generating electricity, now and especially in the future, Kacprowicz said. A few years ago, Columbia Water and Light looked at the books and the projected growth in the demand for energy. Then the bean counters looked at the projected costs. The figures led them to the conclusion that it would be cheaper to give money away — yes, give money away — to residents to help them upgrade their homes and save energy than to buy additional energy.

The city’s utility is a self-funded organization, which means that it is supported not by tax dollars but by utility fees paid by those who use its electricity and water. The money it gives out does not come from the city’s tax coffers but from its own bottom line.

The Home Performance program used in Columbia, Kansas City and St. Louis is sponsored by the US Environmental Protection Agency and the Missouri Department of Natural Resources. It is based on two ideas: Energy savings can be measured scientifically, and trained experts are necessary to guide residents through what can seem like confusing energy challenges.

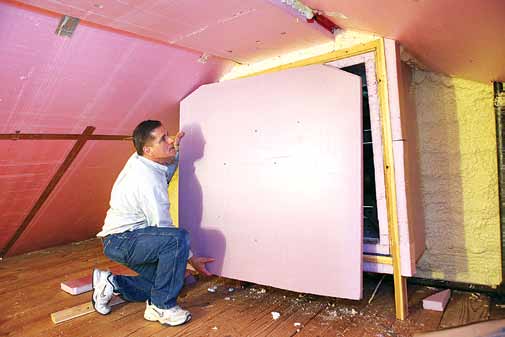

Chandler von Schrader, the national manager of Home Performance with Energy Star at the EPA, said the program provides homeowners with a roadmap for the correct investment in their homes to save energy. The program trains energy auditors, such as Trevor Banning, how to scientifically measure airflow and other factors in a home so they know where a home is losing energy. Each city-approved energy auditor must complete a certification process so he or she can discern where homeowners should spend their money: not just where they should caulk, but whether adding insulation, replacing their furnace, buying better windows or plugging holes is the best use of their dollars.

As von Schrader said, most consumers know something needs to be done, but they don’t know what to do. This program tells them what should be done to help them — and utilities — save energy in the future.

This educational component is crucial, he said.

“We cannot ever let our foot off the accelerator to make sure this demand (for energy savings) is there,” von Schrader said.

The program also requires measurements to ensure the program is working. Before consumers can qualify for the program and incentives, their home must be assessed for energy usage before any work is done. Once qualifying work is done, the home is tested again to ensure the improvements changed the home’s energy usage. According to a city report, homeowners saved an average of 27 percent on their electrical bills. Kacprowicz said some homes have had a 60 percent improvement, including newer homes.

Worker benefits

Kacprowicz said when the city began its program in 2008, contractors weren’t that interested. But then came the housing downturn.

Banning, for example, had been a construction supervisor. Chris Ihler of Energy Link had been doing remodeling and flipping homes. Today, Ihler said, business is good, and he is employing three people full time and four part time.

Becoming certified takes time and effort — and investment. The equipment necessary to ensure the audits provide scientific information — monitors, sensors, an infrared camera and other equipment — can tally upward of $20,000.

At the post-test following the improvements, the energy auditors walk their customers through the paperwork to make sure they get all the financial rebates available. This, too, is crucial. The EPA cited cost as a barrier to consumers improving their homes.

Nor are the energy auditors concerned about running out of work, even if Columbia were to pull the program, which it shows no signs of doing.

Dan Riepe of Home Performance Experts said he thinks the demand for his kind of scientific audit of home energy use will continue.

“The industry is new and constantly growing,” Riepe said. “I’m just going to keep learning new methods and testing more houses.”